1. Executive Summary

This report provides an expert analysis of the Central Bank of Kenya’s (CBK) regulatory framework governing Digital Credit Providers (DCPs) and the broader category of Non-Deposit Taking Credit Businesses (NDTCBs). It examines the official directory of licensed entities and delves into the significant legislative and regulatory shifts that have shaped this dynamic sector. The Kenyan digital credit market has undergone a profound transformation, moving from a largely unregulated space characterized by rapid innovation and significant consumer protection concerns, to a structured environment under the CBK’s increasingly comprehensive oversight. This evolution reflects a regulatory journey from a reactive stance, addressing market excesses, to a more proactive and systemic approach aimed at fostering a fair, transparent, and stable credit market.

Key developments include the enactment of the Central Bank of Kenya (Amendment) Act, 2021, and the subsequent CBK (Digital Credit Providers) Regulations, 2022, which established a formal licensing regime, stringent “fit and proper” criteria for principals, and robust consumer protection mandates. A pivotal change occurred with the Business Laws (Amendment) Act, 2024, which expanded the regulatory perimeter to include all “non-deposit taking credit businesses,” unifying the oversight of various credit providers beyond purely digital channels. This report details these frameworks, the CBK’s licensing activities, enforcement actions, and the collaborative role of other agencies like the Office of the Data Protection Commissioner.

The implications of these regulatory changes are far-reaching. For market participants, the emphasis is on rigorous compliance, enhanced governance, and consumer-centric practices. For consumers, the framework aims to provide greater transparency and protection. The overarching impact on the Kenyan fintech landscape points towards increased regulatory scrutiny, a concerted drive to rebuild consumer trust, and the ongoing adaptation of market players to a more formalized and demanding credit environment. Stakeholders must navigate this evolving terrain with a clear understanding that the CBK is committed to solidifying its supervisory role, suggesting a future of continued regulatory refinement and a focus on sustainable market conduct.

2. The Kenyan Digital Credit Landscape: Growth and Regulatory Genesis

The proliferation of digital lending in Kenya represents one of the most significant developments in its financial sector over the past decade. This explosive growth was largely fueled by the country’s high mobile phone penetration, widespread adoption of mobile money services, and continuous technological advancements.1 The COVID-19 pandemic further accelerated this trend, as demand for accessible and quick credit surged. However, this rapid expansion initially occurred in a regulatory vacuum, with digital lenders operating outside the purview of existing financial sector laws.3

This pre-regulation era, while fostering innovation and expanding financial access for many, became increasingly characterized by serious consumer protection concerns. Reports of predatory lending practices, including exorbitant interest rates and opaque fee structures, became common.1 Unethical debt recovery methods, often involving harassment, intimidation, and public shaming of borrowers, also drew widespread condemnation.1 Furthermore, issues of data misuse, with some lenders accessing and leveraging sensitive personal information without adequate consent, and general borrower harassment, contributed to a growing public outcry.5 This negative public sentiment and the evident harm caused to consumers served as a significant catalyst, creating popular demand for robust regulatory intervention to bring order to the burgeoning sector.3

The Kenyan digital credit market’s evolution is a classic illustration of innovation outpacing regulation. The rapid technological advancements and the ease of deploying digital lending applications allowed the market to scale quickly, but without the necessary safeguards typically associated with traditional financial services. This led to a corrective phase, where the regulatory authorities had to step in to address the emergent risks. The widespread consumer harm observed was not merely a peripheral issue but a primary driver that directly triggered the development of a specific regulatory framework. Recognizing the systemic risks and the erosion of public trust, the Central Bank of Kenya began to lay the groundwork for formalizing the sector. These initial steps were crucial in setting the stage for the landmark Central Bank of Kenya (Amendment) Act, 2021, which marked the official beginning of a new regulatory era for digital credit providers in the country.3 This history underscores the critical importance of developing proactive and adaptive regulatory frameworks, particularly in fast-evolving fintech sectors, to preempt consumer detriment and ensure market stability from the outset.

3. The Central Bank of Kenya’s Directory of Licensed Digital Credit Providers

Accessing and Interpreting the Official List

The Central Bank of Kenya plays a pivotal role in ensuring transparency within the digital credit sector by publishing official directories of licensed Digital Credit Providers (DCPs). These directories, which are updated periodically, serve as the authoritative source for consumers, businesses, and other stakeholders to verify the legitimacy and regulatory standing of DCPs operating in Kenya.8 Access to such a list is fundamental for fostering market confidence and enabling informed decision-making by borrowers. The availability of these directories on the CBK’s official website ensures that the public can readily identify entities that have met the regulator’s stringent requirements.

Snapshot of Licensed Entities and Licensing Trends

The number of licensed DCPs has been a key indicator of the CBK’s progress in formalizing the sector. As of a CBK announcement reported on June 6, 2025, the total number of licensed DCPs had risen to 126.4 This marked an increase from 85 licensed entities reported in October 2024 1, and 32 licensed entities listed in the directory dated November 1, 2023.9 The application process for DCP licenses commenced in March 2022, and since then, the CBK has received a substantial number of applications, exceeding 700, and by some accounts, over 730.1

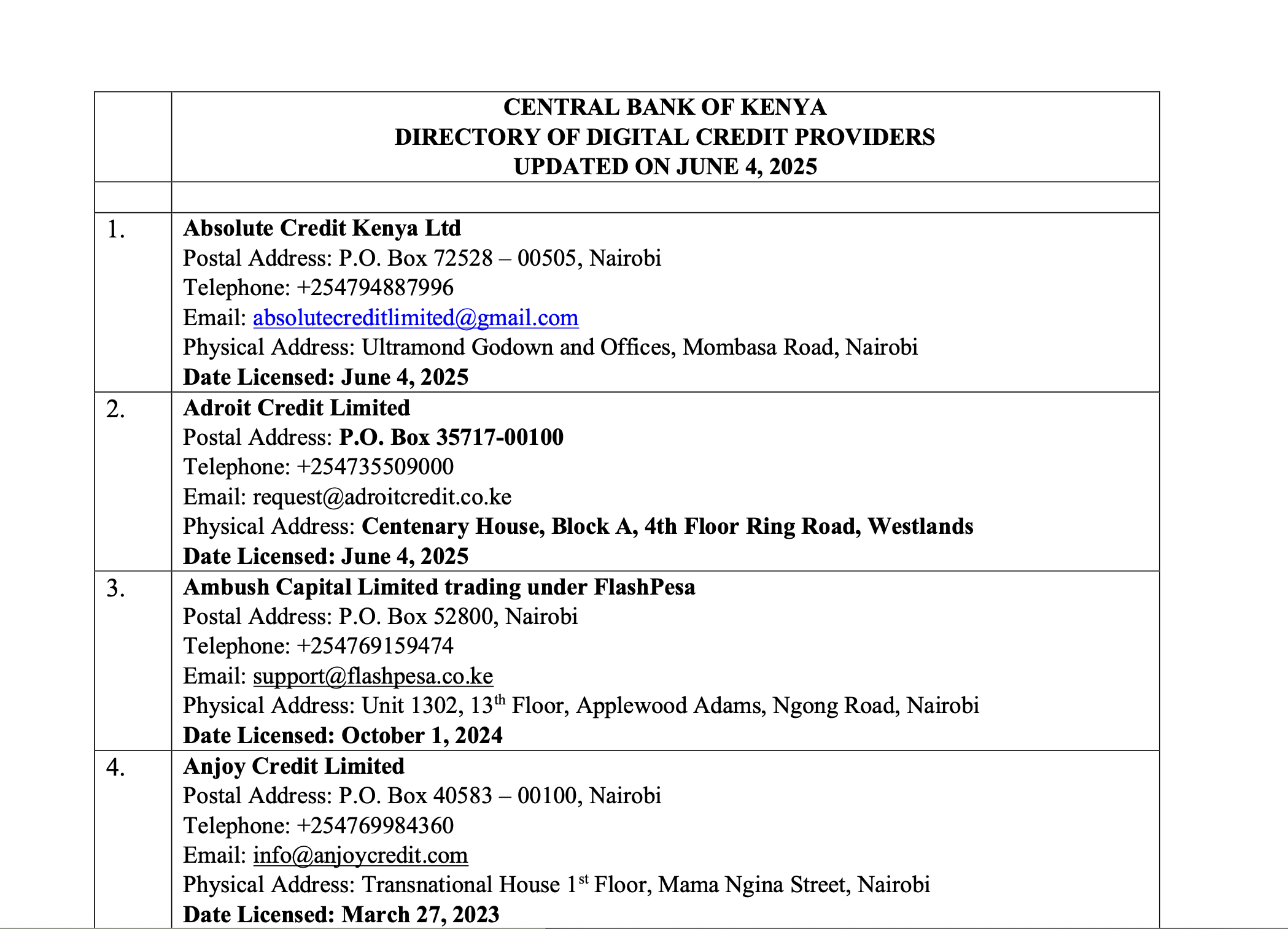

The CBK’s directories provide essential details for each licensed entity, typically including their registered name, postal and physical addresses, telephone numbers, email contacts, and the date they were licensed.8 For example, the document referencing June 2025 lists entities such as Absolute Credit Kenya Ltd and Adroit Credit Limited, both shown as licensed on June 4, 2025, while Ambush Capital Limited (trading as FlashPesa) was licensed on October 1, 2024.8 Similarly, the November 2023 directory included firms like Anjoy Credit Limited and Asante FS East Africa Limited.9 It is important to note that some directory documents, like the one dated June 2025 8, may appear to be forward-looking or illustrative placeholders given the reporting dates of other sources; the information within, however, exemplifies the standard content of such directories.

The progression of licensing is detailed in Table 1 below:

Table 1: Evolution of Licensed Digital Credit Providers in Kenya

| Date of Directory/Report/Announcement | Number of Licensed DCPs | Number of Applications Received (Cumulative since March 2022) | Source(s) |

| November 1, 2023 | 32 | Not explicitly stated for this date, but part of the 700+ pool | 9 |

| October 2024 | 85 | Over 730 | 1 |

| June 6, 2025 (Announcement Date) | 126 | Over 700 | 4 |

The significant disparity between the number of applications received (over 700) and the number of licenses issued (126 by June 2025) underscores the rigorous nature of the CBK’s vetting process. This gap suggests that a considerable number of applicants may not have met the stringent criteria set by the regulator, or had incomplete submissions. Indeed, the CBK has indicated that many applicants were still awaiting approval because they had yet to submit all the required documentation, urging them to do so to expedite the process.4 This meticulous approach, while potentially slowing down the licensing rate, is indicative of the CBK’s commitment to ensuring that only credible and compliant entities are permitted to operate in the digital credit space. Consequently, aspiring DCPs, and subsequently Non-Deposit Taking Credit Businesses (NDTCBs), face a high barrier to entry, necessitating thorough preparation and a commitment to meeting all regulatory standards. While this ensures market integrity, a prolonged licensing process could also inadvertently delay the entry of viable and innovative firms that are slower to meet complex compliance demands.

4. Foundational Regulatory Framework for Digital Lenders

The journey towards a regulated digital lending environment in Kenya was formally initiated with key legislative and regulatory actions spearheaded by the Central Bank of Kenya. These measures aimed to bring order, consumer protection, and stability to a rapidly expanding and previously unchecked sector.

The CBK (Amendment) Act, 2021: Mandate and Objectives

A cornerstone of this regulatory overhaul was the Central Bank of Kenya (Amendment) Act, 2021, which became effective on December 23, 2021.7 This pivotal legislation granted the CBK the explicit legal mandate to license, regulate, and supervise Digital Credit Providers (DCPs) in Kenya.3 The primary objective underpinning this Act was to address the widespread consumer protection concerns that had arisen from the activities of the previously unregulated digital lenders.1 The Act was specifically aimed at curbing predatory lending practices and fostering a fair and non-discriminatory marketplace for access to credit.1

Dissecting the CBK (Digital Credit Providers) Regulations, 2022

Following the enabling legislation, the Central Bank of Kenya (Digital Credit Providers) Regulations, 2022, were issued and became operational on March 18, 2022.7 These regulations provided the detailed operational rulebook for DCPs, outlining the specific requirements and standards they must adhere to. The scope of these regulations is comprehensive, covering areas such as licensing procedures, governance structures, consumer protection mechanisms, data privacy and security, credit information sharing protocols, and Anti-Money Laundering/Combating the Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT) obligations.10

Licensing Prerequisites and “Fit and Proper” Assessments:

The regulations established a stringent licensing regime. Key prerequisites include:

- Corporate Structure: Applicants must be companies incorporated under the Companies Act of Kenya [10 Reg 5(5a), 12].

- Documentation: A comprehensive suite of documents is required for application, including the certificate of incorporation, Memorandum and Articles of Association, a detailed business plan, description of ICT systems and delivery channels, terms and conditions for credit products, AML/CFT policies, data protection policies, evidence of sources of funds, tax compliance certificates, and certificates of good conduct for directors and significant shareholders [10 Reg 5(6), 12].

- “Fit and Proper” Criteria: A critical component of the licensing process is the assessment of key personnel. Directors, Chief Executive Officers, and significant shareholders (those holding 10% or more beneficial interest) must be certified by the CBK as “fit and proper” [10 Reg 5(5b), 13]. This assessment scrutinizes their professional qualifications, relevant experience, integrity, financial probity, and past conduct, explicitly looking for adverse history such as convictions for fraud, involvement in liquidated institutions, or consistent loan defaults.10 The stringency of these criteria directly responds to concerns about the character and competence of individuals previously involved in predatory lending operations, aiming to ensure that only individuals with demonstrable integrity and competence are in control of licensed entities.

- Fees: An application fee of KES 5,000 and an annual license fee of KES 20,000 are stipulated.10

- Non-Transferability: Licenses granted by the CBK are non-transferable and cannot be assigned or encumbered.10

Governance, Risk Management, and Operational Standards:

DCPs are mandated to adhere to sound corporate governance principles, emphasizing ethics, integrity, robust risk management frameworks, and unwavering compliance with all applicable laws.10 This includes the implementation of comprehensive internal policies and procedures covering data protection, AML/CFT, and consumer complaint redress mechanisms.13

Pillars of Consumer Protection:

The regulations place a strong emphasis on safeguarding consumer interests. Key consumer protection provisions, detailed extensively in the draft regulations 10, include:

- Transparency in Pricing: DCPs must clearly and fully disclose all applicable fees, charges, penalties, interest rates, and the methods of their calculation before a credit agreement is entered into. The defined “pricing principles” advocate for customer-centricity, transparency, fairness, equity, and affordability.10

- Prohibition of Deceptive Advertising: Any advertisement published by a DCP must not contain false, misleading, or deceptive representations regarding their services or terms.10

- Consent for Variation of Terms: DCPs cannot unilaterally increase charges or alter credit terms without obtaining explicit customer consent. Furthermore, any changes to their pricing model or parameters require prior written approval from the CBK.10

- Complaints Redress Mechanism: DCPs must establish an accessible and efficient mechanism for handling customer complaints, with a requirement to address such complaints within thirty days of reporting.10

- Ethical Debt Collection: While more explicitly detailed in subsequent amendments related to microfinance, the spirit of prohibiting harassment, threats, violence, or the use of obscene language during debt collection is central to the CBK’s consumer protection stance.15 The initial drive for DCP regulation was significantly motivated by unethical recovery methods.1

- Limitations on Default Listing: New rules also emerged prohibiting the listing of loan defaulters with CRBs for amounts below KES 1,000, aiming to protect borrowers with very small defaults from adverse credit reporting.5

Data Privacy and Security Mandates:

Protecting customer data is a critical aspect of the regulations:

- Confidentiality: DCPs must implement appropriate policies, procedures, and secure systems to ensure the confidentiality and security of customer information and transactions.10

- Customer Consent for Data Sharing: Sharing of customer information with any third party is prohibited without the customer’s explicit consent [10 Reg 12(2), 14].

- Compliance with Data Protection Act: DCPs must comply with the Data Protection Act, 2019. This includes obtaining a registration certificate from the Office of the Data Protection Commissioner (ODPC) as part of the licensing application [10 Reg 5(6q), 1]. The ODPC collaborates with the CBK in the vetting process.4 Some problematic data collection practices, such as indiscriminate access to user contacts, have also been curtailed, partly influenced by platform policies like those implemented by Google for apps on its Play Store.3

Credit Information Sharing (CIS) Mechanisms:

To promote responsible lending and reduce information asymmetry, DCPs are required to:

- Participate in the credit information sharing system by submitting borrower data to licensed Credit Reference Bureaus (CRBs).10

- This system helps lenders make more informed credit decisions and allows good borrowers to distinguish themselves from persistent defaulters, potentially leading to more favorable loan terms.7 The CIS framework in Kenya has evolved from initially sharing only negative information (defaults) to a more comprehensive full-file sharing system, which includes positive credit history.7

AML/CFT Compliance Obligations:

DCPs are subject to anti-money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism requirements:

- They must develop and implement robust AML/CFT policies and procedures [10 Reg 5(6i), 14].

- Compliance with the Proceeds of Crime and Anti-Money Laundering Act, 2009 (POCAMLA) is mandatory.10

The comprehensive nature of this regulatory framework, mirroring many prudential requirements typically applied to traditional deposit-taking financial institutions, signals the CBK’s serious intent to manage the risks associated with the digital credit sub-sector. While the Digital Lenders Association of Kenya (DLAK) initially raised concerns about DCPs being treated akin to prudentially regulated entities, the final regulations, for instance, did not impose capital adequacy requirements on DCPs, a significant concession for the industry.3 Nevertheless, the breadth and depth of the regulations, particularly concerning governance, consumer protection, and data handling, impose a substantial compliance burden. This high threshold can act as a barrier to entry for smaller players or startups, potentially leading to market consolidation or favoring more established firms with greater resources to dedicate to compliance. The regulations also emphasize ongoing supervision and reporting requirements 10, indicating a long-term commitment by the CBK to closely monitor the sector’s conduct and evolution.

Table 2: Key Legislative and Regulatory Milestones for Digital/Non-Deposit Taking Credit in Kenya

| Legislation/Regulation Title | Effective/Operational Date | Key Objectives/Provisions Relevant to DCPs/NDTCBs | Source(s) |

| Central Bank of Kenya (Amendment) Act, 2021 | December 23, 2021 | Empowered CBK to license, regulate, and supervise DCPs; aimed to curb predatory practices and ensure fair credit marketplace. | 3 |

| CBK (Digital Credit Providers) Regulations, 2022 | March 18, 2022 | Provided detailed rules for DCP licensing, governance, consumer protection, data privacy, credit information sharing, and AML/CFT obligations. | 7 |

| Business Laws (Amendment) Act, 2024 | December 27, 2024 | Broadened regulatory scope from “digital credit business” to “non-deposit taking credit business,” unifying the framework for all such providers. | 1 |

5. Navigating the New Frontier: The Business Laws (Amendment) Act, 2024

The regulatory landscape for credit providers in Kenya underwent another significant transformation with the enactment of the Business Laws (Amendment) Act, 2024, which became effective on December 27, 2024.16 This legislation marked a crucial evolution from the initial focus on digital-only lenders to a more encompassing regulatory approach.

Rationale and Key Tenets of the Amendment

The primary rationale behind the 2024 amendment was to broaden the Central Bank of Kenya’s regulatory purview beyond entities solely engaged in “digital” credit. The aim was to create a unified and comprehensive regulatory framework that encompasses all types of non-deposit-taking credit providers, regardless of their operational channels or business models.14 This strategic shift was driven by the need to address emerging credit models that might not have fit neatly under the previous DCP-specific regulations and to ensure consistent oversight across the entire non-deposit-taking credit sector.6 The amendment seeks to level the playing field, enhance consumer protection consistently, and mitigate risks associated with an increasingly diverse credit market.

Redefining the Scope: From “Digital Credit” to “Non-Deposit Taking Credit Business”

A central feature of the Business Laws (Amendment) Act, 2024, was the amendment to the Central Bank of Kenya Act, deleting references to “digital credit business” in key sections like 33S and 57. These terms were replaced with the broader classification of “non-deposit taking credit business” (NDTCB).1 This new, more inclusive category is defined to cover not only the previously regulated digital lenders but also a wider array of credit providers. This includes asset financiers, peer-to-peer (P2P) lenders, businesses offering “buy now, pay later” (BNPL) services, and entities providing credit facilities through traditional, non-digital channels such as cheques or cash, as long as they do not take deposits.14 This effectively brings any entity whose business involves providing credit without accepting deposits under a single, comprehensive regulatory umbrella supervised by the CBK.

Impact on Licensing, Regulation, and Market Participants

The implications of this redefinition are substantial. All entities falling under the newly defined “non-deposit-taking credit provider” category are now required to obtain a license from the CBK and adhere to its comprehensive regulatory requirements.14 This includes compliance with directives on credit pricing models, ethical business practices, robust consumer protection standards, data protection, and AML/CFT measures. The CBK’s powers to supervise these entities have been enhanced, covering aspects like approving business channels and ensuring the integrity of directors and shareholders.14 This expansion significantly increases the number and diversity of businesses subject to direct CBK oversight. Furthermore, the 2024 Act introduced stricter penalties for non-compliance. Businesses can face fines of up to KES 20 million or three times the financial gain from non-compliance, while individuals in contravention could be fined up to KES 1 million.14

Emerging Legal and Operational Considerations

The 2024 amendment, particularly the deletion of the term “digital credit business,” has introduced some legal and operational questions, especially concerning the transitional period for entities previously regulated or applying under the DCP framework.1 Some analyses pointed to a potential “lacuna in the law” regarding the precise status of DCPs whose license applications were pending or those already operating under the 2022 DCP Regulations.1 However, it has also been noted that Section 59 of the CBK Act still appears to mandate that persons who were conducting digital credit business prior to the 2021 CBK (Amendment) Act coming into force, and are not regulated by any other law, must apply for a license from the CBK.1 This suggests an underlying intent to seamlessly transition existing DCPs into the new, broader NDTCB framework rather than creating an unregulated gap. The courts have adopted a stringent interpretation, consistently dismissing claims filed by credit providers found to be operating without the requisite CBK license, reinforcing the necessity of licensing for legal standing and enforceability.1

The 2024 amendment signifies a maturation in Kenya’s regulatory approach to non-bank credit. It represents a shift from a reactive strategy, which narrowly targeted “digital” lenders due to specific, acute problems (such as predatory lending and unethical data practices), to a more proactive, principles-based, and systemic framework. This broader framework is designed to cover all non-deposit-taking credit activities, irrespective of the delivery channel. This evolution is critical because it recognizes that credit provision, whether digital or physical, carries similar inherent risks to consumers and the financial system if left unregulated. By establishing a unified “non-deposit taking credit provider” category, the CBK aims to create a level playing field, prevent regulatory arbitrage—where a business might structure its operations to fall just outside a narrow definition to avoid scrutiny—and ensure consistent consumer protection standards. This is a move from addressing a specific set of problematic symptoms to regulating an entire market segment based on the fundamental nature of the financial activity (i.e., credit provision without deposit-taking). This approach is inherently more sustainable and future-proof, better equipped to handle innovations in credit delivery. The challenges and potential loopholes identified under the DCP-specific regime likely informed the rationale for these more encompassing 2024 amendments.

The legal system is actively reinforcing the CBK’s strengthened licensing mandate. The consistent dismissal of court cases initiated by unlicensed credit providers sends an unequivocal message to the market: operating without a CBK license is untenable and carries significant legal and financial risks. This judicial backing is crucial for the effective enforcement of the new regulatory regime.

Table 3: Comparison of Regulatory Scope: Pre and Post-2024 Business Laws (Amendment) Act

| Regulatory Aspect | Pre-2024 Amendment (DCP Focus – CBK Act 2021 & DCP Regs 2022) | Post-2024 Amendment (NDTCB Focus – Business Laws Amendment Act 2024) | Key Source(s) |

| Definition of Regulated Entity | Primarily “Digital Credit Provider” (DCP) | “Non-Deposit Taking Credit Provider” (NDTCP) / “Non-Deposit Taking Credit Business” (NDTCB) | 1 |

| Scope of Activities Covered | Credit facilities or loan services provided through a digital channel (internet, mobile devices, applications, etc.) | All forms of non-deposit taking credit including: digital loans, physical credit, asset financing, Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL), peer-to-peer (P2P) lending, credit guarantees. | 14 |

| Key Legislation | CBK (Amendment) Act, 2021; CBK (Digital Credit Providers) Regulations, 2022 | Business Laws (Amendment) Act, 2024 (amending the CBK Act and other relevant laws like the Microfinance Act) | 16 |

| Primary Regulatory Focus | Entities offering credit digitally. | All entities offering credit without taking deposits, regardless of the channel. | 14 |

| Penalties for Non-Compliance | Specified under DCP Regulations. | Broadened applicability and potentially increased severity for all NDTCBs (e.g., up to KES 20M for businesses, KES 1M for individuals). | 14 |

6. Key Publications and Scholarly Insights on Kenya’s Digital Credit Ecosystem

Understanding the complex and evolving landscape of digital credit regulation in Kenya requires drawing from a variety of sources. These include official pronouncements from the Central Bank of Kenya, in-depth academic research, practical legal analyses from law firms, and timely media commentary.

Official Pronouncements and Reports from the Central Bank of Kenya

The CBK is the primary source of regulatory information and communicates its actions and policies through several channels. These include official press releases announcing significant developments, such as updates on the number of licensed DCPs/NDTCBs.4 The Bank also publishes foundational regulatory documents, such as the draft Central Bank of Kenya (Digital Credit Providers) Regulations, 2021, for public and stakeholder consultation, which provided a clear view of the intended regulatory direction.10

While the provided materials do not offer direct excerpts from CBK’s Financial Sector Stability Reports specifically detailing the impact of DCP regulation, these reports are identified as bi-annual publications that assess developments, risks, and vulnerabilities in the Kenyan financial sector, and outline policy actions.19 It is reasonable to infer that such significant regulatory interventions would be covered within these comprehensive assessments. A summary of the CBK’s 2023/2024 annual report by a third-party source indicates that the CBK has been actively involved in the licensing and supervision of digital credit providers and has emphasized enhancing due diligence for fraud prevention and compliance.20 Furthermore, reports on the CBK’s monetary policy decisions, such as adjustments to the Central Bank Rate (CBR), provide context on the broader credit environment influenced by the CBK.21 The CBK’s communication regarding DCPs and NDTCBs appears to be primarily through direct regulatory instruments (Acts, Regulations, Guidelines) and official announcements of licensing actions, rather than extensive narrative reports specifically analyzing their market impact within the provided snippets.

Academic Research and Legal Analyses

Scholarly research offers critical perspectives on the effectiveness and implications of regulatory frameworks. A notable example is the Cambridge University Press article analyzing digital microcredit regulation in Kenya.3 This study delves into the CBK (Amendment) Act, 2021, observing that its initial impact on the digital credit landscape was somewhat limited, particularly concerning market conduct and its applicability to dominant bank-led digital credit products like M-Shwari and Fuliza.3 The research highlights the influence of stakeholder groups, such as the Digital Lenders Association (DLAK), during the legislative process and points to an early regulatory emphasis that appeared to privilege prudential aspects over market conduct supervision.3 Such academic work is crucial for understanding the nuanced dynamics of regulatory implementation and the structural power influences within the sector.

Legal commentaries and alerts from prominent law firms provide invaluable, timely analysis of new legislation and regulations. Firms like Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr 1, Bowmans 11, CM Advocates 6, Dentons 15, and Wamae & Allen Advocates 17 have published detailed breakdowns of the CBK (Digital Credit Providers) Regulations and, more recently, the significant changes introduced by the Business Laws (Amendment) Act, 2024. These publications dissect the legal text, explain the rationale behind amendments, and outline the practical implications for businesses operating in or entering the non-deposit-taking credit market. They often provide early warnings of potential legal ambiguities or operational challenges, such as the “lacuna” discussed following the 2024 amendments.1

Industry Perspectives and Media Commentary

News reports from various media outlets play a vital role in disseminating information about regulatory developments to a wider audience. Agencies such as NTV Kenya 5, Capital FM 4, and Ecofin Agency 21 cover CBK announcements regarding licensing numbers, the ongoing vetting process for applicants, and the broader economic context that influences the credit market, including monetary policy changes. These reports often highlight public concerns and the regulator’s responses, contributing to public awareness and accountability.

The interplay between these different sources – official CBK actions, critical academic assessments, practical legal interpretations, and media reporting – creates a rich and multi-faceted public discourse on digital and non-deposit-taking credit regulation. This ecosystem of information provides various viewpoints, allowing for a more holistic understanding of the regulatory landscape. For instance, the tension highlighted by academic research suggesting the initial 2021 Act had “limited changes” in practice 3, despite the CBK’s stated aim of robust consumer protection 1, underscores a potential gap between regulatory intent and perceived or actual early outcomes. The subsequent, broader 2024 amendments may be seen, in part, as an effort to address some of these earlier limitations by casting a wider and more definitive regulatory net. This dynamic underscores the importance for stakeholders to consult a diverse range of information sources to gain a comprehensive understanding of the regulatory environment and its real-world effects, as relying solely on official pronouncements might not reveal the full spectrum of critical perspectives or practical challenges.

7. Market Realities, Regulatory Enforcement, and Ongoing Challenges

The implementation of the regulatory framework for digital and non-deposit-taking credit providers in Kenya has been met with various market realities, robust enforcement actions, and a set of ongoing challenges that continue to shape the sector.

Licensing Statistics and Trends

As previously detailed (Table 1), the licensing process has been characterized by a high volume of applications—over 700 since March 2022—contrasted with a more gradual increase in the number of actual licenses issued, reaching 126 by June 2025.4 The CBK has explicitly stated that a significant number of applicants, estimated to be around 82% at one point, were still awaiting approval primarily because they had not submitted all the required documentation.5 The regulator has consistently urged these applicants to expedite their submissions to complete the licensing process.4 This indicates a meticulous vetting process by the CBK, aimed at ensuring that only entities meeting all stipulated requirements are authorized to operate.

The Role of the Office of the Data Protection Commissioner (ODPC)

The Office of the Data Protection Commissioner plays a crucial and collaborative role in the licensing and supervision of credit providers, particularly concerning data privacy. Compliance with the Data Protection Act, 2019, is a mandatory component of the regulatory framework, and the ODPC works closely with the CBK to vet applicants’ data protection policies and practices.4 Obtaining a certificate of registration from the ODPC is a prerequisite for applying for a CBK license to operate as a credit provider [10 Reg 5(6q)]. Interestingly, in some court cases involving unlicensed credit providers, it was noted that while these entities lacked the primary CBK operational license, they had, in fact, complied with data protection laws and obtained the necessary certificates as data processors or controllers from the ODPC.1 This highlights a multi-layered compliance environment where adherence to one set of regulations (data protection) does not obviate the need for others (CBK licensing for credit provision). It underscores a move towards holistic and interconnected regulatory scrutiny, where the CBK, as the primary gatekeeper for credit operations, relies on assurances from specialized regulators like the ODPC, but retains ultimate authority over the permission to conduct credit business.

Judicial Stance on Unlicensed Operations

The Kenyan judiciary has taken a firm and supportive stance on the CBK’s licensing mandate. Courts, notably the Small Claims Court, have consistently refused to entertain claims filed by credit providers found to be operating without a valid CBK license.1 The rationale articulated in such rulings is that allowing unlicensed entities to use the court system to enforce loan agreements would be “tantamount to sanctioning an illegality”.1 For instance, in the case of M-collect Limited vs. Mbwana Kalua, 139 claims filed by unlicensed DCPs were dismissed on these grounds.1 This judicial backing acts as a powerful enforcement mechanism, significantly raising the stakes for non-compliance and strongly incentivizing businesses to seek and obtain proper licensing to ensure the legal enforceability of their credit agreements and to avoid operational disruption.

Ongoing Challenges

Despite the progress in establishing a regulatory framework, several challenges persist:

- Pace of Licensing: The relatively slow pace of licensing for a large number of applicants remains a concern for the industry, potentially impacting business operations and leading to financial losses for entities awaiting approval.6

- Legal Ambiguities and Transitions: Legislative amendments, such as the 2024 changes that replaced “digital credit business” with “non-deposit taking credit business,” can create temporary legal ambiguities or transitional challenges for market players and the regulator alike. The “lacuna in the law” discussed by some legal analysts post-2024 amendment is an example of such an issue that requires clarification or further regulatory guidance.1

- Balancing Regulation and Innovation: A perennial challenge for regulators is to ensure that the framework effectively curbs harmful practices and protects consumers without unduly stifling legitimate innovation and financial inclusion. The CBK must continuously assess this balance as the market evolves.

- Supervisory Capacity for an Expanded Scope: The shift to regulating all NDTCBs significantly broadens the CBK’s supervisory responsibilities, encompassing a more diverse range of business models and a larger number of entities. Ensuring adequate supervisory capacity and expertise to effectively monitor this expanded sector is crucial for the long-term success of the regulatory regime.

These market realities and challenges indicate that while the foundational regulatory structure is largely in place, its implementation and adaptation will be an ongoing process requiring vigilance from the CBK, cooperation from the industry, and continued support from the legal system.

8. Strategic Analysis and Implications for Stakeholders

The evolving regulatory framework for digital and non-deposit-taking credit in Kenya carries significant strategic implications for various stakeholders, including credit providers, consumers, investors, and the broader fintech ecosystem. The overarching trend points towards a more formalized, transparent, and consumer-centric credit market.

For Existing and Aspiring Credit Providers

The foremost implication is the unequivocal necessity of obtaining and maintaining a license from the Central Bank of Kenya under the now broadened Non-Deposit Taking Credit Business (NDTCB) framework.14 The era of operating in a regulatory grey area is definitively over. Aspiring entrants and existing players transitioning to the new regime must meticulously prepare for the licensing process. This involves a thorough understanding of the expanded scope of regulated activities, ensuring that leadership and significant shareholders meet the stringent “fit and proper” criteria 10, and establishing robust internal systems and policies. These must comprehensively cover consumer protection, data privacy (in line with ODPC requirements), transparent pricing, ethical debt collection, and effective AML/CFT measures.10 The financial and legal consequences of non-compliance are severe, including the legal unenforceability of loan agreements, substantial monetary penalties, and reputational damage.1 The regulatory changes are likely to drive a “flight to quality,” where well-governed, compliant, and consumer-focused credit providers will be better positioned to thrive, while entities unable or unwilling to meet these heightened standards may be forced to exit the market or significantly re-engineer their operations.

For Consumers

The enhanced regulatory framework is designed to offer greater protection and empowerment to consumers of credit services. Key benefits include increased transparency in loan terms and conditions, with full disclosure of all costs and charges.10 Consumers can expect fairer treatment from credit providers, particularly concerning debt collection practices, and stronger safeguards for their personal data.14 The regulations also mandate clear avenues for dispute resolution, providing consumers with mechanisms to address grievances.10 A critical tool for consumers is the CBK’s Directory of Licensed Credit Providers, which allows them to verify the legitimacy of a lender before engaging their services. Increased awareness of their rights under the new regulatory regime will be crucial for consumers to fully benefit from these protections.

For Investors

For investors, the evolving regulatory landscape in Kenya’s credit market presents both opportunities and considerations. Increased regulatory clarity and oversight can reduce uncertainty and perceived risk, potentially making the sector more attractive for investment. However, the stringent licensing requirements and ongoing compliance obligations mean that investors must conduct thorough due diligence on the regulatory standing, governance structures, and operational integrity of any credit provider they consider partnering with or investing in.20 The expansion of regulation to cover all NDTCBs broadens the potential investment landscape to include diverse models like BNPL and P2P lending, but it also means that regulatory risk assessment must cover a wider array of compliance areas. The increased capital requirements for traditional banks 16, though not directly applicable to NDTCBs in the same way, could also influence the overall funding environment and competition for capital.

For the Broader Fintech Ecosystem

The CBK’s move towards comprehensive regulation of all non-deposit-taking credit businesses signals a maturation of the Kenyan fintech ecosystem. This regulatory posture is likely to encourage higher operational standards across the board and may foster greater trust in the formal financial sector, including fintech-driven solutions.14 It could also lead to market consolidation as smaller players find the costs and complexities of compliance challenging, potentially leading to mergers, acquisitions, or partnerships with larger, licensed entities. Innovation in credit products and delivery channels will continue, but it will need to occur within the clearly defined boundaries set by the new regulatory parameters. The emphasis on robust governance and consumer protection may also spur innovation in areas like RegTech (regulatory technology) and ethical AI in credit scoring.

Overall, the Kenyan digital and non-deposit-taking credit market is expected to see increased professionalism and potentially less fragmentation as regulatory enforcement solidifies. This could, in the long run, make the sector more sustainable and attractive for responsible, long-term investment and innovation that genuinely serves the financial inclusion agenda while protecting consumers.

9. Concluding Remarks and Future Outlook

The Central Bank of Kenya has demonstrably moved to establish a robust and increasingly comprehensive framework for the regulation of digital credit providers, a scope now significantly broadened to encompass all non-deposit-taking credit businesses. This regulatory journey, from an initially laissez-faire environment characterized by rapid, unchecked growth to a structured supervisory regime, has been swift and largely responsive to the emergent market challenges and consumer protection imperatives. The legislative milestones, including the CBK (Amendment) Act, 2021, the CBK (Digital Credit Providers) Regulations, 2022, and the pivotal Business Laws (Amendment) Act, 2024, collectively signify a paradigm shift towards greater accountability, transparency, and stability in this vital segment of Kenya’s financial sector.

Looking ahead, the future will likely involve continued refinement and adaptation of these regulations as the market evolves, new financial products emerge, and technological advancements present fresh opportunities and challenges. The full impact of the 2024 amendments, which significantly expanded the CBK’s regulatory mandate, will unfold over time as more entities come under its direct supervision. Key areas to monitor will include the CBK’s capacity to effectively supervise this broader and more diverse range of non-deposit-taking credit businesses. The success of this expanded regulatory regime will heavily depend on the CBK’s supervisory resources, its agility in adapting to ongoing market innovations within the NDTCB space, and its ability to maintain a constructive dialogue with the industry. The existing Risk-Based Supervisory (RBS) framework employed by the CBK may offer a foundation for managing these diverse entities 7, but may require further enhancement.

Furthermore, the actual impact of these regulations on consumer protection levels, financial inclusion, and the overall health of the credit market will warrant ongoing assessment. Striking the right balance between fostering innovation that expands access to credit and ensuring market stability, consumer welfare, and systemic integrity will remain a critical objective for the regulator.1 There may be a continuing need for capacity building within the CBK and for clear communication channels with the industry to ensure that regulations are practical, achieve their intended outcomes, and do not inadvertently stifle beneficial financial innovation.

The Kenyan experience in regulating its dynamic fintech-driven credit market offers valuable insights and potential lessons for other jurisdictions across Africa and beyond that are grappling with similar challenges of balancing innovation with regulation in the digital age. The commitment to a formalized, transparent, and consumer-centric credit environment positions Kenya as a key market to watch in the evolution of financial sector governance.

📚 References: Digital Credit Providers in Kenya

- CBK licenses 41 more digital lenders – NTV Kenya

- The fate of digital credit providers after CBK Act amendments – Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr

- The Rise of Non-Deposit-Taking Credit Providers – CM Advocates

- Bank Supervision – Central Bank of Kenya (CBK)

- CBK Directory of Licensed Digital Credit Providers

- CBK Digital Credit Providers Directory – Updated Version

- Central Bank of Kenya 2024 Financial Report – Prembly Blog

- Kenya: Digital Credit Providers Regulations, 2021 – Bowmans

- Kenya Lowers Key Rate to Support Credit Growth – Ecofin Agency

- Digital Credit Provider Licence Application – eProcedures Kenya

- How to Obtain a Digital Credit Provider Licence – Capita Registrars

- Kenya Enacts Business Laws (Amendment) Act, 2024 – EY

- Loan Recovery Options for Non-Compliant Credit Providers – CM Advocates

- Digital Credit Providers in Kenya Rises to 126 – Capital FM

- Implications of Business Laws (Amendment) Act, 2024 – Wamae & Allen

- Business Laws (Amendment) Act, 2024 – Bowmans

- Legal Alert: Business Laws (Amendment) Act 2024 – Dentons HHM

- Digital Microcredit Regulation in Kenya – Cambridge University Press

- Digital Credit Providers Regulations, 2021 – CBK

- Financial Sector Stability Reports – CBK