Five Presidential Defeats, One Transformative Legacy: How Kenya’s Eternal Opposition Leader Reshaped a Nation

Introduction: The Handshake

On March 9, 2018, Kenya awoke to a political earthquake. On the steps of Harambee House, the nation’s seat of executive power, stood two men who had, for the better part of a year, brought the country to a standstill with their bitter rivalry. President Uhuru Kenyatta, whose recent election victory had been nullified by the Supreme Court before he won a controversial re-run, stood beside his arch-nemesis, Raila Odinga. Odinga had boycotted that re-run and subsequently staged his own mock inauguration as the “People’s President”.1 Now, they were shaking hands.

This moment, which became known simply as “The Handshake,” was more than a peace accord; it was the quintessential expression of Raila Odinga’s confounding political character.1 Here was the man who could mobilize mass resistance, channel popular fury against the state, and push the nation to the very brink of collapse, only to pivot with breathtaking speed towards a pragmatic, elite-level pact. The Handshake encapsulates the dualities that have defined his half-century in public life: the fiery activist and the calculating insider; the champion of the masses and the consummate power broker; the political prisoner who would later serve the regime that jailed him.4

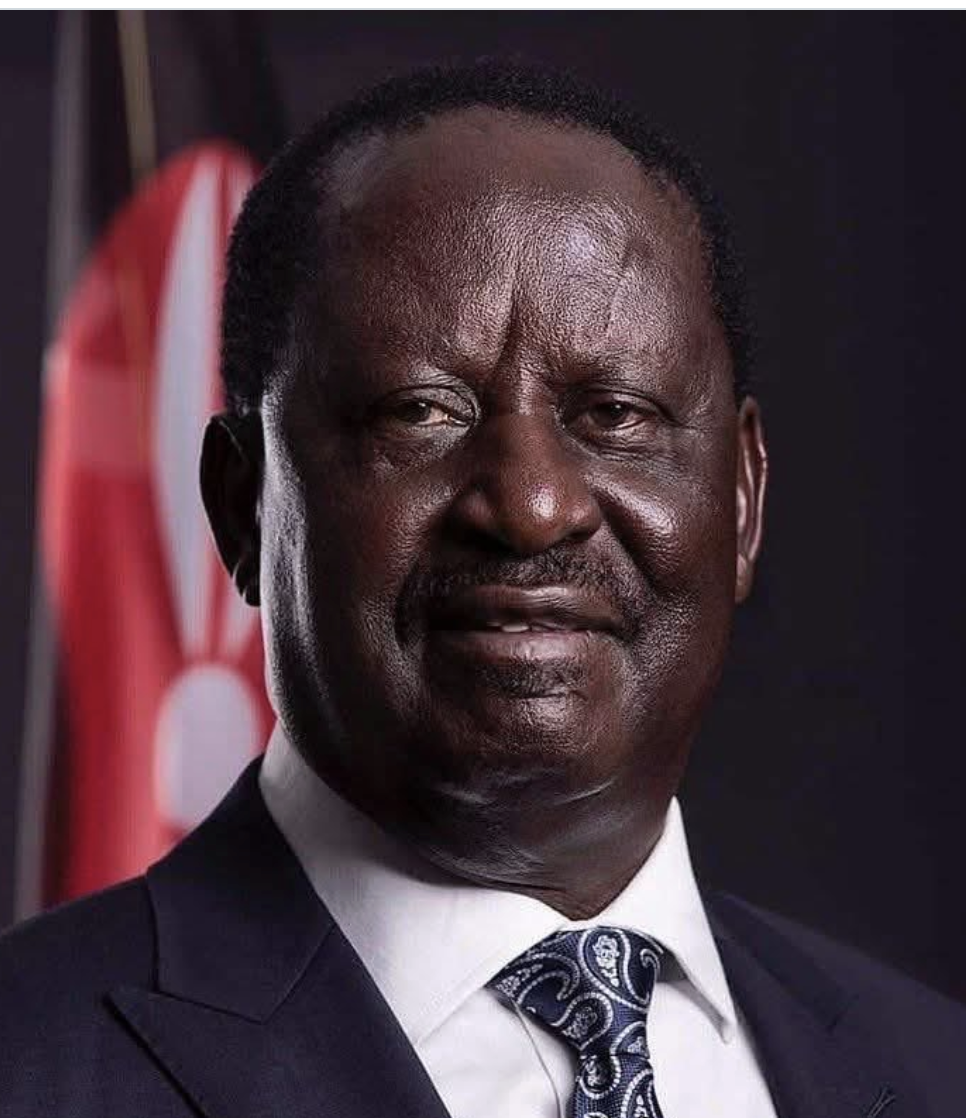

His career has been a long, winding odyssey marked by imprisonment, exile, ministerial appointments, five unsuccessful presidential bids, and a prime ministership born from the ashes of post-election violence. He is an enigma, a figure who inspires messianic devotion and deep-seated distrust in equal measure. This has raised a central, defining question about his role in Kenya’s history: Is his career a consistent, principled struggle for democracy, repeatedly thwarted by entrenched interests? Or is it a series of brilliant tactical maneuvers in a relentless, single-minded pursuit of the presidency? This report seeks to unravel the life and times of Raila Amolo Odinga, to understand the nature of his impact on Kenya’s turbulent political development, and to assess the legacy of the man they call Agwambo—The Mystery.

Part I: The Making of a Dissident (1945-1991)

1: In the Shadow of Jaramogi

Raila Amolo Odinga was born into the crucible of Kenyan politics on January 7, 1945, in Maseno, to Mary Juma and Jaramogi Oginga Odinga.5 His father was not merely a politician but a towering figure in the nationalist struggle, a man whose legend was forged in the fight for independence. As a scion of this political dynasty and a member of the Luo ethnic group, Raila’s path was, in many ways, preordained.5 His childhood home was a hub of political activity, where “lengthy political discussions” were the norm, steeping him in the language and strategy of liberation politics from a young age.9

The ideological influence of his father was profound and lasting. Jaramogi, a courageous and perceptive leader, famously rejected a colonial-era offer to become president, insisting that Jomo Kenyatta first be released from prison.9 After independence, he became Kenya’s first Vice President, but his tenure was short-lived. A fierce Pan-Africanist with socialist leanings, he clashed with the pro-Western, capitalist orientation of Kenyatta’s government, resigned in 1966, and spent the rest of his life as the country’s most prominent opposition figure.10 The arc of Jaramogi’s career—from the pinnacle of power to the political wilderness—drew a blueprint that his son would follow with uncanny fidelity. It was a political inheritance, a dynastic pattern of challenging the state from both within its highest echelons and from the outside as its most formidable opponent.

This dynastic mission is best captured by the title of Jaramogi’s 1967 autobiography, Not Yet Uhuru.11 The phrase, meaning “Not Yet Freedom” in Swahili, encapsulated his belief that formal independence from Britain had not delivered true freedom to the Kenyan people. He argued that the post-colonial state, with its “brutal oppression of opposition,” had merely replaced one set of masters with another.11 This idea of an unfinished “second liberation”—a struggle for economic justice, equitable power-sharing, and genuine constitutionalism—became the foundational script for Raila Odinga’s own career. His life’s work can be seen as the continuation of his father’s unfinished political project, a perpetual quest to achieve the “Uhuru” that Jaramogi believed was still out of reach.

2: The Engineer from Magdeburg

After his early schooling at Kisumu Union Primary and Maranda High School, Raila took a path that set him apart from his peers in Kenya’s nascent political elite. In 1962, he dropped out of school and traveled to East Germany, a world away from the Anglophone educational networks that shaped most of the country’s post-colonial leadership.6 He first attended the Herder Institution at the University of Leipzig to learn German before receiving a scholarship in 1965 to the Technical School in Magdeburg, now part of Otto von Guericke University.5 In 1970, he graduated with a Master of Science in Mechanical Engineering.6

Life behind the Iron Curtain provided a unique and formative education. As a Kenyan student in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) during the Cold War, he occupied a privileged space that allowed him to traverse the ideological divide. He could visit West Berlin through Checkpoint Charlie, a journey he used to smuggle goods unavailable in the East for his friends, giving him a practical lesson in navigating complex, rigid systems.5 This experience in East Germany endowed him with a distinct technocratic skillset and a non-Western political-economic perspective. While many of his contemporaries were steeped in the traditions of British or American universities, Odinga was exposed to socialist models of state planning and industrialization. This different lens likely informed his later ideological leanings towards social democracy and state-led welfare programs.5 This background contributes to his political enigma: he is at once a populist “man of the people” and a highly trained technocrat; a product of a socialist state who would become a successful capitalist entrepreneur.5 This blend of technical pragmatism and ideological flexibility became a hallmark of his political style.

3: Prisoner Number 2052

Upon his return to Kenya in 1970, Odinga embarked on a career that combined academia and public service. He worked as a lecturer in the Department of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Nairobi before joining the Kenya Bureau of Standards (KeBS) in 1974, where he rose to the position of Deputy Director by 1978.7 Throughout this period, he remained politically active, supporting calls for government reform in an increasingly authoritarian state.7

His life changed irrevocably on August 1, 1982. Following a failed coup attempt against President Daniel arap Moi by junior officers of the Kenya Air Force, Odinga was arrested and accused of being one of the masterminds.5 He was charged with treason but was ultimately detained without trial for six years.6 A biography published decades later, apparently with his approval, suggested his involvement was deeper than he had previously admitted.5 This period of imprisonment was a crucible that transformed him from a technocrat with political leanings into a national symbol of resistance. The state’s persecution, intended to neutralize him, paradoxically conferred upon him the legitimacy and “struggle credentials” that his inherited name alone could not provide.

His years in detention were harrowing. He endured solitary confinement and immense psychological strain, exemplified by the profound pain of learning of his mother Mary’s death in 1984, a fact his jailers withheld from him for two months.5 His detentions became a recurring feature of his life under the Moi regime. After his release in February 1988, he was re-arrested just months later in September for his pro-democracy agitation.5 Released again in June 1989, he was incarcerated for a third time in July 1990 alongside other multiparty advocates like Kenneth Matiba and Charles Rubia.5 During this time, Amnesty International adopted him as a prisoner of conscience, recognizing him as a leading supporter of multi-party democracy in Kenya.14

By making him a political prisoner, the state elevated his stature. His suffering created a powerful narrative of personal sacrifice for a national cause, connecting his story to the broader struggle for a “second liberation”.4 It was during this period that his political followers christened him Agwambo, a Luo term for “The Mystery” or “The Unpredictable”.5 His ability to survive the state’s onslaught made him an almost mythical figure. Finally released in June 1991, he fled to Norway in October of that year amid credible threats of a government assassination plot, only to return in February 1992 to join the burgeoning multiparty movement.5

Part II: The Art of the Possible (1992-2007)

4: The Second Liberation

Raila Odinga’s return to Kenya in 1992 coincided with the dawn of the country’s multiparty era, a change he had sacrificed years of his life to bring about. He immediately plunged into the political fray, joining the Forum for the Restoration of Democracy (FORD), the main opposition movement led by his father.5 In the 1992 general election, he won the parliamentary seat for Langata constituency in Nairobi, a diverse urban area that he would represent for the next two decades.6

The opposition, however, was fractious. FORD soon split into two factions: FORD-Kenya, led by Jaramogi Odinga, and FORD-Asili, led by Kenneth Matiba.5 Following his father’s death in January 1994, Raila vied for the leadership of FORD-Kenya but lost to Michael Wamalwa Kijana in a contentious party election. In a move that would become characteristic, he did not remain where he felt his ambitions were stifled. He resigned from the party his father had led and joined the smaller National Development Party (NDP).5

Using the NDP as his new political vehicle, Odinga made his first bid for the presidency in the 1997 general election. In a crowded field of fifteen candidates, he finished a respectable third, behind the incumbent Daniel arap Moi and Democratic Party leader Mwai Kibaki.5 He garnered 667,886 votes, or 10.79% of the total, while successfully defending his Langata parliamentary seat.17 The election once again highlighted the weakness of a divided opposition, which campaigned on the country’s struggling economy and endemic corruption but failed to coalesce around a single candidate to unseat Moi.19

5: A Deal with the Devil?

Following the 1997 election, Odinga made a political calculation that stunned the nation and redefined his public image. In a “surprise move,” he led his NDP into a partnership with President Moi’s ruling Kenya African National Union (KANU)—the very party and leader responsible for his years of detention.5 For many of his staunchest supporters and fellow veterans of the “second liberation,” this was an unforgivable betrayal, a capitulation to the despot he had once fought.4

This alliance, however, reveals a core element of Odinga’s political strategy: a willingness to engage in radical pragmatism, even at the cost of ideological purity, in the belief that true power can only be captured or reformed from within. He was not abandoning his ambition; he was changing his tactics. The cooperation deepened, and in 2001, Odinga was appointed to Moi’s cabinet as Minister for Energy.7 The following year, the NDP officially merged with KANU to form “New KANU,” and Odinga was elected as the powerful Secretary-General of the newly combined party.5

The endgame of this gambit was clear: Odinga was positioning himself to succeed the constitutionally term-limited Moi as the KANU presidential candidate in the 2002 elections.7 He sought to capture the formidable KANU political machine from the inside. The plan was shattered, however, when Moi, in a fateful decision, bypassed his new Secretary-General and endorsed Uhuru Kenyatta, the son of Kenya’s first president, as his chosen successor.7 This maneuver demonstrated Odinga’s capacity for complex political calculation, but also its limits, solidifying his reputation as Agwambo, the unpredictable strategist.

6: The Orange Revolution

Betrayed by Moi, Odinga did not retreat. Instead, he orchestrated one of the most significant political realignments in Kenyan history. Protesting Moi’s choice, he led a mass exodus of powerful KANU figures, forming a faction known as the “Rainbow Alliance,” which soon became the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP).7 In a masterstroke of coalition-building, Odinga’s LDP joined forces with an opposition alliance led by Mwai Kibaki, the National Alliance of Kenya (NAK), to form the National Rainbow Coalition (NARC).9

Odinga became the kingmaker of the 2002 election. When Kibaki was seriously injured in a car accident during the campaign, Odinga stepped up, campaigning relentlessly across the country and securing a landslide victory for NARC that finally ended KANU’s 40-year grip on power.7 The victory, however, was built on a promise that would soon be broken. A pre-election Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) had reportedly stipulated a power-sharing arrangement, including the creation of a new, powerful Prime Minister post for Odinga.7

Once in office, President Kibaki reneged on the agreement. Odinga was appointed Minister of Roads, Public Works, and Housing, a significant but far cry from the executive power he had been promised.5 This political betrayal set the stage for the next chapter of his career. He found his battlefield in the 2005 constitutional referendum. The government-backed draft constitution was seen by many as a tool to consolidate presidential power, contrary to the NARC campaign’s promise of devolution.5 Odinga seized the opportunity, transforming a personal political grievance into a popular national cause.

He masterfully led the “No” campaign, whose official symbol was an orange. The campaign galvanized national opposition to the proposed constitution, which was decisively rejected by voters with a 57% to 43% margin.5 This victory was a stunning rebuke to President Kibaki and demonstrated Odinga’s exceptional ability as a political mobilizer. In the aftermath, a furious Kibaki sacked Odinga and his LDP allies from the cabinet.5 The split was complete. Riding the wave of popular support from the referendum, Odinga took the “Orange” symbol and forged it into a new, formidable political party: the Orange Democratic Movement (ODM).10 He had successfully rebranded himself as the nation’s foremost defender of constitutionalism and set the stage for his strongest presidential bid yet.

Part III: The Pinnacle and the Precipice (2007-2022)

7: A Nation on the Brink

The 2007 general election was the culmination of the political forces unleashed by the 2005 referendum. The contest pitted President Mwai Kibaki, running under the newly formed Party of National Unity (PNU), against Raila Odinga, the undisputed leader of the ODM. The campaign was fiercely contested and deeply polarizing, with political mobilization occurring largely along ethnic lines.21 Odinga, a Luo, built a broad multi-ethnic coalition, while Kibaki’s support was concentrated among his Kikuyu community and its allies.21 Throughout the campaign, a succession of over 50 opinion polls consistently placed Odinga in the lead, fueling expectations of a historic victory.21

As the election results began to trickle in on December 27, 2007, they initially confirmed these expectations, showing Odinga with a commanding lead.21 The ODM declared victory on December 29. However, as the Electoral Commission of Kenya (ECK) continued to announce results, the gap inexplicably narrowed. Amid widespread and credible claims of vote-rigging and irregularities, the ECK declared Kibaki the winner by a slim margin of about 232,000 votes.21 International observers deemed the process “flawed,” and an exit poll commissioned by the US, released later, suggested Odinga had actually won by a comfortable 6% margin.21

The announcement ignited a firestorm of violence. Protests in opposition strongholds quickly degenerated into horrific, ethnically-charged clashes across the country. The 2007-2008 post-election violence (PEV) was the darkest chapter in Kenya’s independent history, a period of brutal killings, sexual violence, and mass displacement.24 In the end, over 1,100 people were killed and more than 350,000 were forced from their homes.25

As the nation teetered on the brink of full-scale civil war, the international community, led by the African Union, intervened. A mediation team headed by former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan began 41 days of intense negotiations.26 In a moment of crucial statesmanship, Odinga agreed to the talks, subordinating his claim to the presidency in the interest of national survival.9 The result was the National Accord and Reconciliation Act of 2008, a power-sharing agreement that created a Grand Coalition Government and pulled Kenya back from the precipice.26

8: The Prime Minister

On April 17, 2008, Raila Odinga was sworn in as the second Prime Minister of Kenya, a position resurrected after being abolished in 1964.5 The Grand Coalition Government he entered was a product of necessity, a “coalition of the unwilling,” as Odinga himself admitted.20 The cabinet was bloated, with a record 40 ministers and 52 deputy ministers, its portfolios split evenly between Kibaki’s PNU and Odinga’s ODM to reflect the power-sharing deal.20

Governing under such circumstances was fraught with challenges. The five-year term was marked by persistent infighting, public spats, and deep-seated suspicion between the two camps. Major disagreements erupted over everything from the appointment of public officials to the hierarchy of government protocol.28 This internal paralysis often stymied progress, particularly on sensitive issues like tackling corruption and ensuring accountability for the post-election violence.28

Despite the dysfunction, the coalition government managed to deliver landmark achievements. The shared existential threat of national collapse and intense international pressure created a narrow window for fundamental change. The government’s most significant accomplishment was overseeing the drafting and promulgation of a new, progressive Constitution in 2010. This constitution, which Odinga had campaigned for alongside Kibaki, fulfilled a long-held dream of the reform movement by establishing a devolved system of government with 47 counties, a robust bill of rights, and a more independent judiciary.7 Odinga also leveraged his position to introduce a “performance contracting system” to enhance accountability and strategic planning within government ministries.31 The coalition also made significant strides in infrastructure development and judicial reform.28 This experience demonstrated both the potential and the inherent limitations of elite pacts. While the coalition averted civil war and delivered a new constitution, its internal paralysis on other key issues highlighted that sharing power does not automatically resolve the underlying conflicts that cause political crises.

9: The Trials of Democracy

After his term as Prime Minister, Raila Odinga would contest the presidency three more times, with each election further entrenching the role of the judiciary as the final arbiter of Kenya’s contentious politics.

In 2013, he ran under the banner of the Coalition for Reforms and Democracy (CORD), with his former rival Kalonzo Musyoka as his running mate.7 The CORD manifesto promised the full implementation of the new constitution, job creation, and broad social and economic reforms.33 He faced Uhuru Kenyatta, his former cabinet colleague in the Moi government. In an election that was largely peaceful, Kenyatta was declared the winner with 50.07% of the vote, just enough to avoid a run-off. Odinga received 43.31%.32 Citing numerous irregularities, Odinga challenged the result at the newly empowered Supreme Court. The court upheld Kenyatta’s victory, and in a crucial moment for the country’s democratic maturation, Odinga accepted the verdict.32

The 2017 election was a rematch. Odinga led a new, broader coalition, the National Super Alliance (NASA), again with Musyoka as his running mate.5 The NASA manifesto focused on national reconciliation, strengthening devolution, and implementing the long-ignored Truth, Justice, and Reconciliation Commission (TJRC) report to address historical injustices.37 When the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) declared Kenyatta the winner with 54% of the vote, Odinga’s team alleged a massive fraud, claiming the electoral servers had been hacked to maintain a consistent gap between the two candidates.5

Once again, Odinga turned to the Supreme Court. This time, in a decision that reverberated across Africa, the court, led by Chief Justice David Maraga, agreed with the petitioners. By a 4-2 majority, it nullified the presidential election, citing substantial “irregularities and illegalities” that affected the integrity of the vote.40 It was the first time a presidential election had been overturned by a court on the continent. However, Odinga’s victory was short-lived. Arguing that the IEBC had not been sufficiently reformed to guarantee a fair contest, he boycotted the court-ordered re-run in October 2017.1 This allowed Kenyatta to win with 98% of the vote amid low turnout, plunging the country back into a political crisis. In a final act of defiance, Odinga staged a symbolic swearing-in ceremony in January 2018, declaring himself the “People’s President,” setting the stage for the dramatic Handshake that would follow just weeks later.1

| Year | Political Coalition/Party | Running Mate | Key Opponent | Official Result (Votes & Percentage) | Outcome/Aftermath |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1997 | National Development Party (NDP) | N/A | Daniel arap Moi (KANU) | 667,886 (10.79%) | Finished 3rd. Later formed a coalition with Moi’s KANU party.5 |

| 2007 | Orange Democratic Movement (ODM) | N/A | Mwai Kibaki (PNU) | 4,352,993 (44.07%) | Disputed results led to post-election violence. Became Prime Minister in a Grand Coalition Government.21 |

| 2013 | Coalition for Reforms and Democracy (CORD) | Kalonzo Musyoka | Uhuru Kenyatta (Jubilee) | 5,340,546 (43.31%) | Lost election. Supreme Court upheld results; Odinga conceded.32 |

| 2017 | National Super Alliance (NASA) | Kalonzo Musyoka | Uhuru Kenyatta (Jubilee) | 6,822,812 (44.94%) | Supreme Court nullified the election. Boycotted the re-run. Led to the 2018 “Handshake”.39 |

| 2022 | Azimio la Umoja–One Kenya Coalition | Martha Karua | William Ruto (UDA) | 6,942,930 (48.85%) | Narrowly lost election. Supreme Court upheld results; Odinga accepted the ruling.42 |

10: The Bridge to Nowhere

The 2018 Handshake with President Kenyatta was not just an end to a crisis but the beginning of a new, ambitious political project: the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI).1 The two leaders established a task force to diagnose and propose solutions to nine of Kenya’s most persistent challenges, chief among them the “winner-take-all” political system that made every election a high-stakes, ethnically charged conflict.44

The BBI’s final report proposed a raft of constitutional amendments designed to expand the national executive and make it more inclusive. Key proposals included the re-introduction of a Prime Minister, two Deputy Prime Ministers, and the creation of an official Leader of the Opposition, a post that would be filled by the runner-up in the presidential election.46 It was, in essence, an attempt to institutionalize the logic of the 2008 Grand Coalition and prevent future post-election crises by ensuring the losing side had a formal stake in the government.

The initiative, however, faced fierce opposition, most notably from Deputy President William Ruto, who framed it as a self-serving pact between two political dynasties. The BBI’s fate was ultimately sealed in the courts. In a series of landmark rulings, the High Court, Court of Appeal, and finally the Supreme Court in March 2022 declared the entire process unconstitutional.7 The judiciary’s core finding was that the President cannot initiate a constitutional amendment through a “popular initiative,” a route reserved exclusively for ordinary citizens. The bridge Odinga and Kenyatta had tried to build had led nowhere.44

Undeterred, Odinga launched his fifth and seemingly final presidential campaign for the 2022 election. This time, he ran under the Azimio la Umoja–One Kenya Coalition, in an ironic twist of fate, with the full backing of the incumbent president, Uhuru Kenyatta.1 With veteran reformer Martha Karua as his running mate, he campaigned on a platform of social protection, including a universal healthcare program dubbed “Baba Care,” and a renewed fight against corruption.43 In a tight race, he was narrowly defeated by William Ruto, garnering 48.85% of the vote to Ruto’s 50.49%.42 His subsequent petition to the Supreme Court was dismissed, and, true to his word, he pledged to respect the court’s ruling, bringing his long quest for the presidency to a close.5

Part IV: An Assessment of the Man and His Legacy

11: The Odinga Doctrine

To understand Raila Odinga is to understand a political ideology that is both deeply felt and remarkably fluid. At its core, his philosophy can be described as a form of social democracy, rooted in a stated concern for the oppressed, the poor, and the equitable distribution of public resources.9 This aligns with his policy proposals over the years, such as advocating for cash-transfer programs for the poor and suspending taxes on essential goods during economic downturns.5 Yet, this progressive economic stance is sometimes coupled with a more conservative line on social issues, such as his past controversial statements on LGBT rights, which reflect a pragmatism that is often attuned to prevailing public sentiment.5

His true genius, however, lies in his political communication. He is a master of rhetoric, employing powerful metaphors to frame his political quests in epic, almost biblical terms. He is the biblical Joshua, leading his people on a long journey to “Canaan,” the promised land of political power and prosperity.48 This narrative skill creates a deep, emotional bond with his followers and elevates his campaigns from mere political contests to moral crusades. This connection is reflected in the affectionate nicknames he has earned: Baba (Father), a term of respect and endearment; Tinga (Tractor), for his political forcefulness; and the ever-present Agwambo (The Mystery).5

Away from the political stage, Odinga is also a formidable businessman. This intersection of political and economic power is most evident in the family-owned company, East African Spectre.7 Founded by Raila in 1971, the company became the sole manufacturer of liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) cylinders in Kenya.5 Over the years, the Odinga family, with his wife Ida serving as Managing Director, has expanded its business interests, diversifying into the midstream petroleum market with plans for a major fuel depot, as well as ventures in ethanol and fertilizer production through another firm, Spectre International.51 This business acumen underscores the complex reality of a man who is both a champion of the poor and a member of the country’s wealthy elite. His personal life is anchored by his long marriage to Ida Odinga, with whom he has had four children.6

The Enigma’s Enduring Impact

Assessing the legacy of Raila Odinga is an exercise in confronting paradox. He is, without question, one of the most consequential figures in modern Kenyan history. His name is synonymous with the “second liberation,” the decades-long struggle that dismantled the one-party state and ushered in an era of multiparty democracy.4 He has been the “definitive political mobiliser,” a central actor in every major political event that has shaped Kenya for over thirty years, from the restoration of multipartyism in 1991 to the peaceful transition of power in 2002 and the delivery of a new constitution in 2010.9 His persistent legal challenges to election results have, ironically, been instrumental in strengthening the independence of Kenya’s judiciary.

Yet, this legacy of democratic expansion is inextricably linked to periods of profound national instability. The same quests for power that aimed to reform the state have, on multiple occasions, been the trigger for the country’s most severe political crises. His challenge to the 2007 election results led to the darkest chapter of post-independence violence, and his defiance after the 2017 election brought the nation to another dangerous precipice.1

Ultimately, Raila Odinga’s legacy is that of the indispensable opposition figure who fundamentally expanded Kenya’s democratic space, yet whose personal inability to capture the presidency and whose methods of challenging those losses repeatedly tested the nation’s resilience. He is the revolutionary who forced the system to bend, but who never managed to break through to the highest office. As he pursues a new role on the continental stage with his bid for the African Union Commission Chairmanship, he leaves behind a Kenyan political landscape that he both built and battled, a nation shaped in the image of his own complex, contradictory, and transformative journey.5 He remains, to the very end, Agwambo.

Appendix

Career Timeline: Key Positions Held

| Position | Years in Office | Administration | Key Responsibilities/Achievements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Member of Parliament, Langata | 1993 – 2013 | Moi, Kibaki | Represented a diverse urban constituency; initiated poverty-alleviation and education projects like the Kibera slum upgrading.5 |

| Minister for Energy | 2001 – 2002 | Daniel arap Moi | Served in the cabinet as part of the KANU-NDP merger, overseeing the national energy portfolio.5 |

| Minister of Roads, Public Works, and Housing | 2003 – 2005 | Mwai Kibaki | Appointed after the NARC victory; oversaw infrastructure projects before being dismissed after the 2005 referendum.5 |

| Prime Minister of Kenya | 2008 – 2013 | Mwai Kibaki (Grand Coalition) | Co-managed the government under the National Accord; oversaw the promulgation of the 2010 Constitution and introduced performance contracting in ministries.28 |

| AU High Representative for Infrastructure Development | 2018 – 2023 | African Union | Appointed after the “Handshake” to champion infrastructure projects across the continent.1 |

Reference

- 2018 Kenya handshake – Wikipedia, accessed October 15, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2018_Kenya_handshake

- en.wikipedia.org, accessed October 15, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raila_Odinga#:~:text=Having%20lost%20the%202017%20election,part%20in%20government%20decision%20making.

- The Handshake that Shaped a Nation – Kenya Connection, accessed October 15, 2025, https://kenyaconnection.org/the-handshake-that-shaped-a-nation/

- From a Tiger to a Cat: How and Why Raila Odinga betrayed the Liberation Cause 35 Years Later | Democracy in Africa, accessed October 15, 2025, https://democracyinafrica.org/from-a-tiger-to-a-cat-how-and-why-raila-betrayed-the-liberation-cause-35-years-later/

- Raila Odinga – Wikipedia, accessed October 15, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raila_Odinga

- Raila Amolo Odinga | Daily Nation, accessed October 15, 2025, https://nation.africa/kenya/people/raila-amolo-odinga-3809512

- Raila Odinga | Age, Previous Offices, Education, Mother, & Family | Britannica, accessed October 15, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Raila-Odinga

- Who are Raila Odinga’s mother and father? – Britannica, accessed October 15, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/question/Who-are-Raila-Odingas-mother-and-father

- Citation on Raila.pdf – UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI, accessed October 15, 2025, https://www.uonbi.ac.ke/sites/default/files/Citation%20on%20Raila.pdf

- Raila Amolo Odinga – Oxford Reference, accessed October 15, 2025, https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/oi/authority.20110810105518704

- Jaramogi Oginga Odinga – Wikipedia, accessed October 15, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jaramogi_Oginga_Odinga

- Jaramogi Oginga Odinga: The Man Kenya Can Never Forget – The Elephant, accessed October 15, 2025, https://www.theelephant.info/analysis/2019/01/31/jaramogi-oginga-odinga-the-man-kenya-can-never-forget/

- Raila Amolo Odinga – The World Economic Forum, accessed October 15, 2025, https://www.weforum.org/people/raila-amolo-odinga/

- AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL, accessed October 15, 2025, https://www.amnesty.org/fr/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/afr320071991en.pdf

- Kenya: Raila Odinga, a prisoner of conscience – Amnesty International, accessed October 15, 2025, https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/afr32/007/1991/en/

- Kenya – Moi, Politics, Economy – Britannica, accessed October 15, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/place/Kenya/Mois-rule

- 1997 Kenyan general election – Wikipedia, accessed October 15, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1997_Kenyan_general_election

- en.wikipedia.org, accessed October 15, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raila_Odinga#:~:text=In%20his%20first%20bid%20for,position%20as%20the%20Langata%20MP.

- KENYA: parliamentary elections Bunge – National Assembly, 1997, accessed October 15, 2025, http://archive.ipu.org/parline-e/reports/arc/2167_97.htm

- making power sharing work: kenya’s grand coalition cabinet, 2008–2013, accessed October 15, 2025, https://successfulsocieties.princeton.edu/sites/g/files/toruqf5601/files/LS_Kenya_Powersharing_FINAL.pdf

- 2007 Kenyan general election – Wikipedia, accessed October 15, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2007_Kenyan_general_election

- A stolen election | Leader – The Guardian, accessed October 15, 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2007/dec/31/leadersandreply.mainsection1

- Kenya Presidential Elections 2007 | Research Starters – EBSCO, accessed October 15, 2025, https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/politics-and-government/kenya-presidential-elections-2007

- Post-Election Crisis in Kenya and Internally Displaced Persons: A Critical Appraisal, accessed October 15, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257142282_Post-Election_Crisis_in_Kenya_and_Internally_Displaced_Persons_A_Critical_Appraisal

- Post-election Violence in Kenya and its Aftermath | Smart Global …, accessed October 15, 2025, https://www.csis.org/blogs/smart-global-health/post-election-violence-kenya-and-its-aftermath

- The 2007-08 Post-Election Crisis in Kenya: A Success Story for the Responsibility to Protect? (Chapter 1) – Cambridge University Press, accessed October 15, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/responsibility-to-protect/200708-postelection-crisis-in-kenya-a-success-story-for-the-responsibility-to-protect/584265F268C499A500125DA9F7C80713

- Elections in Kenya in 2007 – GOV.UK, accessed October 15, 2025, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a79936940f0b642860d9284/elections-ke-2007.pdf

- Grand Coalition leaves behind chequered legacy – Business Daily, accessed October 15, 2025, https://www.businessdailyafrica.com/bd/economy/grand-coalition-leaves-behind-chequered-legacy-2029244

- en.wikipedia.org, accessed October 15, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raila_Odinga#:~:text=Raila%20Amolo%20Odinga%20(7%20January,Opposition%20in%20Kenya%20since%202013.

- Government of National Unity (Kenya) – Wikipedia, accessed October 15, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Government_of_National_Unity_(Kenya)

- Raila Odinga – Innovations for Successful Societies – Princeton University, accessed October 15, 2025, https://successfulsocieties.princeton.edu/interviews/raila-odinga

- Raila Odinga – Kenyan Politician, 2013 Elections, Opposition Leader …, accessed October 15, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Raila-Odinga/2013-elections

- CORD-Manifesto-2013.pdf, accessed October 15, 2025, https://learning.uonbi.ac.ke/courses/GPR203_001/document/Property_Law_GPR216-September,_2014/CORD-Manifesto-2013.pdf

- IPU PARLINE database: KENYA (National Assembly), ELECTIONS IN 2013, accessed October 15, 2025, http://archive.ipu.org/parline-e/reports/arc/2167_13.htm

- Kenya’s Odinga accepts defeat – DW – 03/30/2013, accessed October 15, 2025, https://www.dw.com/en/kenyan-court-upholds-kenyatta-election-odinga-concedes/a-16710263

- National Super Alliance – Wikipedia, accessed October 15, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Super_Alliance

- NASA-Manifesto-2017.pdf – Amazon S3, accessed October 15, 2025, https://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3.sourceafrica.net/documents/118488/NASA-Manifesto-2017.pdf

- Battle line drawn as NASA and Jubilee launch their Manifestos – YouTube, accessed October 15, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yoq84D7_ScQ

- 2017 Kenyan general election – Wikipedia, accessed October 15, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2017_Kenyan_general_election

- Raila Amolo Odinga and Another v Independent Electoral and …, accessed October 15, 2025, https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1012&context=scr

- History of Kenya – Wikipedia, accessed October 15, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Kenya

- Presidential Elections 2022 | Kenya Elections, accessed October 15, 2025, https://elections.nation.africa/

- 2022 Kenyan general election – Wikipedia, accessed October 15, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2022_Kenyan_general_election

- 2021 Kenyan constitutional referendum attempt – Wikipedia, accessed October 15, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2021_Kenyan_constitutional_referendum_attempt

- Kenya’s BBI is the political elite’s attempt to rewrite history | Uhuru Kenyatta | Al Jazeera, accessed October 15, 2025, https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2019/11/30/kenyas-bbi-is-the-political-elites-attempt-to-rewrite-history

- HIGHLIGHTS OF THE REPORT OF THE BUILDING BRIDGES INITIATIVE TASK FORCE, accessed October 15, 2025, http://umanyi.makueni.go.ke/storage/publications/GoMC-KM-2025-8527.pdf

- Ex-rivals Ruto and Odinga tussle for power in new alliance | Article – Africa Confidential, accessed October 15, 2025, https://www.africa-confidential.com/article/id/15401/ex-rivals-ruto-and-odinga-tussle-for-power-in-new-alliance

- The Manifestation of Ideology in the Metaphors used by Kenyan Politician Raila Odinga – Biblioteka Nauki, accessed October 15, 2025, https://bibliotekanauki.pl/articles/2196167.pdf

- The woman who gave Raila the name ‘Agwambo’ -The Standard, accessed October 15, 2025, https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/evewoman/amp/news/article/2001453419/the-woman-who-gave-raila-the-name-agwambo

- Raila firm, oil company seek out of court agreement – The Standard, accessed October 15, 2025, https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/business/busia/article/1144014759/raila-firm-oil-company-seek-out-of-court-agreement

- Ida Odinga – Wikipedia, accessed October 15, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ida_Odinga

- Odinga family targets oil market with Sh300m depot – Business Daily, accessed October 15, 2025, https://www.businessdailyafrica.com/bd/corporate/companies/odinga-family-targets-oil-market-with-sh300m-depot-2070496

- The African Union Commission Chair Elections; Examining Kenya’s Previous Bid and the Prospects for Victory – HORN International Institute for Strategic Studies, accessed October 15, 2025, https://horninstitute.org/the-african-union-commission-chair-elections-examining-kenyas-previous-bid-and-the-prospects-for-victory/