The Man with a National Blueprint

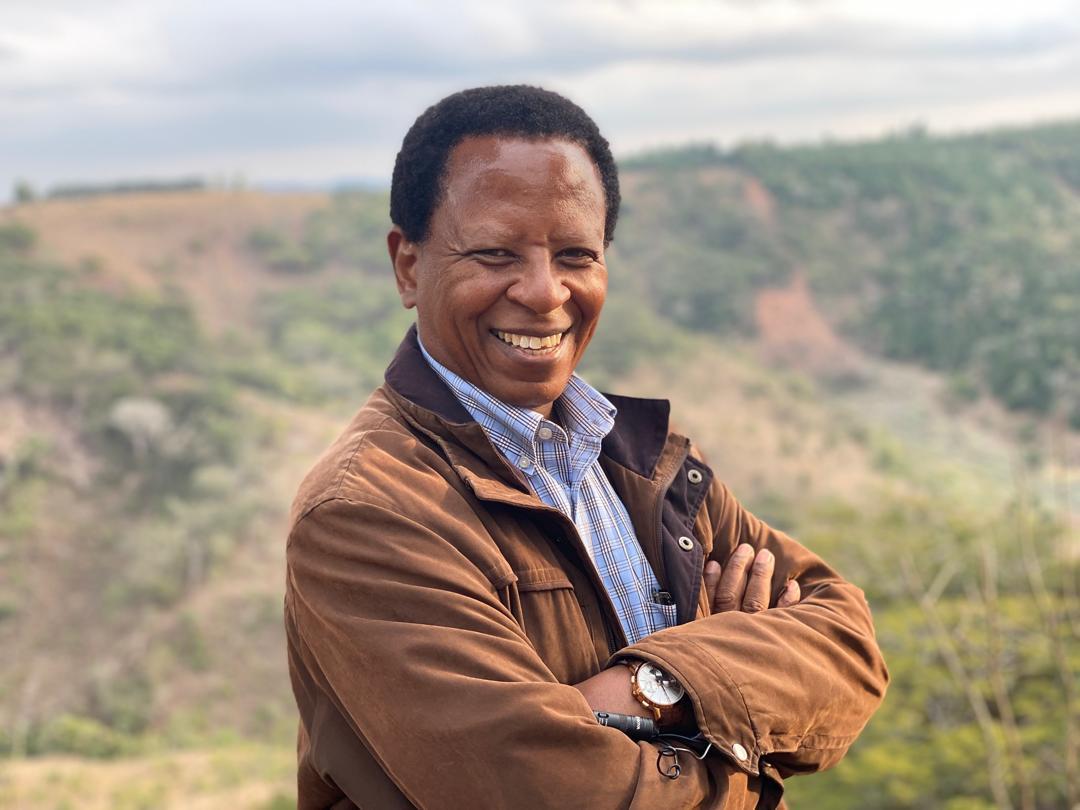

In the intricate tapestry of Tanzania’s economic development, agriculture has long been the dominant thread, a sector employing the majority of its people yet chronically underperforming its potential. For decades, the narrative was one of subsistence, low yields, and unrealized promise. Yet, over the past decade, a quiet but profound revolution has been taking root, cultivated not in the fields alone but in boardrooms, ministerial offices, and international forums. At the heart of this transformation is Geoffrey Kirenga, a figure who embodies the critical nexus of public policy, private capital, and grassroots development.

As the long-serving Chief Executive Officer of the Southern Agricultural Growth Corridor of Tanzania (SAGCOT) Centre, Kirenga has steered a regional experiment into a nationally celebrated success. Now, he stands at the helm of its most ambitious evolution: the expansion from a single corridor into the Agricultural Growth Corridors of Tanzania (AGCOT), a nationwide framework poised to redefine the country’s economic destiny.1 This transition, mandated at the highest levels of government, is more than a mere scaling-up; it is the institutionalization of a new philosophy for development, one built on the power of partnership and pragmatic, evidence-driven leadership.

This report argues that Geoffrey Kirenga’s consistent, trust-based leadership and his masterful orchestration of a complex public-private partnership (PPP) have forged a proven, scalable model for agricultural transformation. This model has not only delivered remarkable results in its initial phase but has now been adopted as the national vehicle to achieve Tanzania’s most ambitious development goals, including the visionary Agriculture Master Plan 2050.1 To understand the future of Tanzanian agriculture is to understand the journey of SAGCOT and the doctrine of its chief architect. By tracing the origins of the initiative, dissecting Kirenga’s unique leadership philosophy, quantifying the staggering impact of the past decade, and analyzing the strategic expansion to AGCOT, this report will illuminate the blueprint that is turning Tanzania’s agricultural potential into a pillar of national prosperity.

Chapter 1: Sowing the Seeds of a Revolution – The Genesis of SAGCOT

The Pre-2011 Landscape: A Sector in Waiting

To grasp the magnitude of SAGCOT’s impact, one must first appreciate the landscape from which it grew. In the years leading up to 2011, Tanzania’s economy was in a state of transition. Since 1985, it had been moving from a planned to a market-based economy, a shift that brought growth but also initial hardship; GDP per capita only surpassed its pre-transition figure around 2007.5 Agriculture was, and remains, the backbone of the economy, but it was a backbone under immense strain. The sector generated roughly a quarter of the country’s GDP and was the primary source of employment for an estimated 65% to 75% of the population.6

Despite this demographic dominance, the sector was characterized by deep-seated challenges. Productivity was low, with the vast majority of cultivation carried out by smallholder farmers dependent on rain-fed, subsistence methods.9 There was a significant “missing middle”—a dearth of medium-scale commercial farmers to bridge the gap between smallholders and a few large-scale plantations.8 Critical infrastructure, from rural roads to irrigation and electricity, was underdeveloped, leaving farmers isolated from markets and unable to add value to their produce. While Tanzania was largely self-sufficient in staple foods like maize, it remained a major importer of key commodities such as wheat and, critically, edible oils, of which nearly 80% were imported.8 The potential was immense—vast tracts of arable land and favorable climates—but it was locked away behind systemic barriers.

A Vision Born from Dialogue

The catalyst for change emerged from a growing consensus within Tanzania that agriculture needed to be treated not as a social sector, but as a primary engine of economic growth. This philosophy was crystallized in the government’s Kilimo Kwanza (‘Agriculture First’) initiative, a policy framework that recognized the urgent need for modernization and commercialization.11 Crucially,

Kilimo Kwanza emphasized that the government could not achieve this transformation alone. It called for a new era of strategic collaboration between the public and private sectors.

This principle of partnership was institutionalized through forums like the Tanzania National Business Council, where dialogues between government officials and private sector leaders began to shape a new, shared vision.12 It was from these conversations that the concept of a geographically focused, investment-driven “growth corridor” was born—an idea to concentrate resources in a high-potential region to create a critical mass of activity and unlock its latent potential.

The Davos Moment: A Global Stage for a Tanzanian Idea

The concept of an agricultural growth corridor was elevated from a national strategy to a globally recognized development model in January 2011. At the World Economic Forum’s annual meeting in Davos, Switzerland, then-President Jakaya Kikwete presented the vision for the Southern Agricultural Growth Corridor of Tanzania to an audience of global leaders, investors, and development partners.6 This was a masterstroke of economic diplomacy. By launching the initiative on such a prominent stage, Tanzania signaled its seriousness, attracted immediate international attention, and positioned SAGCOT as a pioneering public-private partnership in African agriculture.12

The international community responded with enthusiasm. The corridor was officially launched in Dar es Salaam in May 2011, accompanied by the unveiling of the SAGCOT Investment Blueprint (IBP).11 This document was the operational heart of the vision, outlining specific investment opportunities, defining the institutional framework, and identifying the steps needed to de-risk the corridor for private capital. The initial vision was ambitious: to bring 350,000 hectares of land into profitable production, transition 100,000 smallholders into commercial farmers, and generate USD 1.2 billion in annual farming revenues by 2030.15

The core of the blueprint was the “cluster” model, centered on a nucleus-outgrower concept. The strategy envisioned large-scale, land-based investments—such as plantations and processing factories—serving as “nuclei” of development. These anchor investments would provide technology, stable markets, and expertise, which would then radiate outwards to surrounding smallholder farmers integrated into the value chains as outgrowers.6 This was a direct attempt to solve the “missing middle” problem by creating symbiotic relationships between large and small players, all supported by coordinated public investment in essential infrastructure like roads, rail, and energy along the corridor’s central spine.6

Resilience Through Shifting Political Tides

The journey of SAGCOT from its high-profile launch to its current status as a national flagship program was not a simple, linear progression. Its survival and ultimate triumph are a testament to the resilience of its underlying structure, a quality that was tested through significant shifts in Tanzania’s political economy.

Under the administration of President Kikwete, who championed its launch, SAGCOT received strong government support and was hyped by the international community as a groundbreaking model.6 However, the subsequent regime of President John Magufuli (2015-2021) ushered in a different development philosophy, one characterized by a strong focus on resource nationalism and large-scale, state-led infrastructure projects. During this period, the private-sector-centric, donor-supported SAGCOT model received less political attention and, as one academic analysis notes, “all but disappeared” from the national discourse.6

The fact that the initiative endured this period of relative “negligence” is profoundly significant. It demonstrates that the PPP model, by its very nature, created a robust and distributed network of stakeholders that was not dependent on a single source of political patronage. The SAGCOT Centre Ltd., established as a neutral coordinating body, continued its work, supported by a diverse coalition of private sector partners, civil society organizations, and international development partners like the UK’s FCDO, USAID, and the World Bank.13 This diverse support base provided the institutional ballast needed to weather the political storm.

The ascension of President Samia Suluhu Hassan in 2021 marked another dramatic shift. Her administration revitalized the focus on private sector collaboration and foreign investment. Recognizing the proven track record that SAGCOT had quietly built, President Hassan did not merely continue the project; she elevated it. Her directive in March 2023 to expand the model nationwide was a powerful validation of its success and a strategic decision to make it the central pillar of her government’s agricultural transformation agenda.11 This political trajectory—from international hype to domestic neglect and finally to national adoption—reveals a crucial lesson: a well-designed PPP, with a broad and committed stakeholder base, can create a level of institutional resilience that allows a long-term development vision to survive short-term political cycles. Geoffrey Kirenga’s ability to navigate these changing tides and keep the partnership focused on its mission was a critical element of this resilience.

Chapter 2: The Kirenga Doctrine – A Philosophy of Pragmatic Leadership

The success of a complex, multi-stakeholder initiative like SAGCOT cannot be attributed to its design alone. A blueprint requires an architect, and a partnership requires a trusted facilitator. Since 2013, Geoffrey Kirenga has been that architect and facilitator, a leader whose unique background and pragmatic philosophy have become inextricably linked with the initiative’s identity and achievements. His leadership style, built on trust, evidence, and relentless facilitation, provided the “human infrastructure” necessary to make the PPP model work in practice.

The Technocrat’s Transition: Bridging Two Worlds

Kirenga’s profile is not that of a typical corporate CEO. He is a scientist by training, holding a Master of Science in Entomology from the Imperial College of the University of London, with deep expertise in crop promotion, pest management, and plant protection.21 Before joining SAGCOT, he was a quintessential public servant, serving as the Director of the Crop Development Division at the Tanzania Ministry of Agriculture, Food Security and Cooperatives.22 This background gave him immense credibility within the government and a granular understanding of the policy landscape and the on-the-ground realities of Tanzanian agriculture.

His transition in 2013 to lead the SAGCOT Centre Ltd.—a predominantly private-sector-led entity—was a move he reportedly approached with a “sense of apprehension.” This personal journey from public service to a private-sector-facing role perfectly mirrors the bridge that SAGCOT itself was designed to build. He had to learn to speak the language of business, to understand the risk calculations of investors, while retaining the trust of his former colleagues in government. This dual fluency became his greatest asset, allowing him to translate the needs of agribusiness to policymakers and articulate the government’s development vision to potential investors. He became the living embodiment of the public-private partnership.

The “Honest Broker”: A Doctrine of Trust and Facilitation

At the core of the Kirenga doctrine is the concept of the SAGCOT Centre as an “honest facilitator” and “impartial” convener.2 In a landscape populated by actors with diverse and often conflicting interests—government ministries focused on regulation, private companies on profit, development partners on specific outcomes, and civil society on social welfare—the Centre could not be seen as just another player. It had to be the neutral ground where these interests could converge toward a common goal.

Kirenga cultivated this role with meticulous care. He understood that for the partnership to function, it required more than just a shared objective; it needed a framework of mutual trust and accountability. This was achieved through mechanisms like “partnership compacts,” formal agreements that clearly outlined the roles, responsibilities, and commitments of each stakeholder in a given value chain or cluster. As Kirenga explained, “The compacts created ownership and accountability, fostering trust and commitment among stakeholders”.12 This approach transformed vague goodwill into concrete, actionable plans.

He also established clear, non-negotiable principles for private sector engagement. To be a SAGCOT partner was not merely to invest in the corridor, but to buy into its philosophy. Kirenga articulated three core conditions: “businesses must operate in food and nutrition value chains, address smallholder farmers’ needs, and demonstrate sustainable practices”.12 This framework ensured that private investment was aligned with the initiative’s public interest goals of food security, inclusivity, and environmental stewardship, filtering out purely extractive ventures and building a coalition of partners committed to the broader vision.

Evidence-Based Advocacy: Data as a Tool for Change

A defining feature of Kirenga’s leadership is his pragmatic, evidence-based approach to advocacy. Rather than relying on rhetoric, he has consistently used data and tangible evidence to make the case for policy and infrastructure reforms. The most powerful illustration of this method is the story of how SAGCOT influenced the creation of the Tanzania Rural and Urban Roads Agency (TARURA).

Recognizing that poor rural roads were a primary bottleneck preventing farmers from getting their produce to market, Kirenga’s team took a direct approach. “We took cameras to capture the plight of farmers whose produce was rotting due to poor roads,” he recalled. “That evidence convinced the government to act”.12 The visual proof of economic loss was more compelling than any policy paper. The result was the establishment of TARURA and a new policy directing 30% of its budget specifically to rural road development, a monumental win for the agricultural sector. This victory was not an isolated incident. The same focused, evidence-driven advocacy led to other key reforms, such as VAT exemptions on critical inputs and the creation of Private Sector Desks within ministries to provide a direct channel for resolving business challenges.12 This doctrine of “show, don’t just tell” built immense credibility for the SAGCOT Centre and demonstrated its value as a practical problem-solver for both government and industry.

An Unstated Philosophy of Adaptive Leadership

While Kirenga has not published a formal leadership manifesto, his actions align closely with modern theories of adaptive and emotionally intelligent leadership.23 His acknowledgment of his initial “apprehension” reflects a high degree of self-awareness, a cornerstone of emotional intelligence. His success is built on “relational capital”—the extensive network of trust he has cultivated across the Tanzanian and international agribusiness communities.21 He has demonstrated the ability to “thrive in challenging environments,” most notably by steering the initiative through the politically fallow years of the Magufuli administration.23

His leadership is a case study in influencing without direct authority. The SAGCOT Centre has no legal mandate to enforce its principles; its power comes from its ability to convene, persuade, and build consensus.25 Kirenga has consistently demonstrated the ability to move with ease between high-level strategic thinking—articulating the grand vision of agricultural transformation—and the on-the-ground tactics needed to achieve it, from negotiating tax policy to diagnosing a bottleneck in a specific value chain.23 This combination of vision, diplomacy, and pragmatism has been the essential software that allowed the hardware of the PPP framework to deliver on its extraordinary promise.

Chapter 3: The Harvest of a Decade – Quantifying the SAGCOT Success Story

After more than a decade of implementation, the SAGCOT initiative under Geoffrey Kirenga’s leadership has transitioned from a promising blueprint to a proven model with a remarkable and quantifiable track record. The results, which in many cases have surpassed the original 20-year targets in just over 10 years, provide a compelling, data-driven case for the effectiveness of the corridor approach. The success can be measured across four key pillars: investment mobilization, farmer empowerment, environmental sustainability, and policy reform.

The Engine of Growth: Mobilizing Billions in Capital

The foundational goal of SAGCOT was to create an environment so attractive and de-risked that it would catalyze a massive inflow of both public and private capital. On this front, the achievement has been staggering. By 2024, the initiative had mobilized a cumulative USD 6.34 billion in investments within the corridor, a figure that represents 111% of its target and was achieved five years ahead of the 2030 schedule.1

The composition of this investment reveals the strategic logic of the public-private partnership. The vast majority, USD 5.02 billion (79.2%), came from the public sector.4 This was not a subsidy but a strategic deployment of capital into enabling infrastructure—upgrading roads, extending the electrical grid to rural areas, and developing irrigation schemes. This massive public investment served as the catalyst, creating the stable, predictable operating environment that private capital requires. Consequently, the private sector responded, committing

USD 1.32 billion (20.8%) to agribusinesses, processing facilities, and value chain development.4 This nearly 4:1 ratio of public to private investment demonstrates a successful de-risking model, where government spending effectively “crowds in” private investment rather than displacing it.

From Subsistence to Surplus: Empowering a Million Farmers

The ultimate measure of SAGCOT’s success lies in its impact on the lives of Tanzania’s smallholder farmers. The initiative has reached over 1 million smallholder farmers since its inception, integrating them into inclusive value chains and providing them with access to training, modern inputs, and reliable markets.1 In the 2024 fiscal year alone, SCL-facilitated partners engaged with 102,657 farmers.

This engagement has translated into a dramatic economic transformation. While comprehensive revenue data across all one million farmers is complex to aggregate, targeted monitoring shows exponential growth. Annual farming revenues for farmers participating in specific partner programs surged from USD 42.9 million in 2019 to USD 255.3 million in 2024—a fourteenfold increase. Another report from 2022 noted a 17% year-over-year increase in smallholder incomes, with female farmers experiencing the highest gains, a significant step toward gender equity in the sector.28 Beyond income, the initiative has been a powerful engine for job creation, generating over

253,000 new jobs in farming, processing, logistics, and other allied services, providing a vital boost to rural livelihoods.1

These aggregate numbers are brought to life by tangible successes in specific value chains. In the Iringa and Njombe clusters, potato productivity skyrocketed from an average of 7 tons per hectare to over 20 tons, with some modern farms exceeding 40 tons.12 The Southern Highlands, once a non-player in the avocado market, now leads the country in exports. The dairy sector has been revolutionized, with partner companies like ASAS Dairies increasing daily milk processing from 15,000 liters to 400,000 liters.12 These are not marginal improvements; they are transformative shifts that have turned subsistence farmers into commercial producers. Stories of individuals like Mussa, who found a gateway out of poverty through a stable market for his tomatoes, and Kayusi Musigwa, who built a thriving dairy business thanks to a local milk collection center, underscore the profound human impact of the model.17

The Green Backbone: Championing Sustainability

From its inception, SAGCOT was designed to prove that agricultural growth does not have to come at the expense of the environment. Under Kirenga’s leadership, this commitment to sustainability was operationalized through a robust framework for Inclusive Green Growth (IGG). The results have been exceptional, with 1,285,404 hectares of land being managed using Climate-Smart Agriculture (CSA) practices by 2024, a figure that dramatically surpasses the 2030 target of 350,000 hectares.28

A cornerstone of this effort is the IGG guiding tool, developed through a multi-stakeholder collaboration that included key environmental partners like CARE International and the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF).29 This tool provides a practical framework for agribusinesses to assess and improve their performance against three core principles: Inclusivity and Social Sustainability, Business Sustainability, and Environmental Sustainability.32 Its adoption has been widespread, with 88% of surveyed farmer organizations and agro-industries applying its principles. This work is guided by the Green Reference Group (GRG), a unique advisory body co-chaired by the government and the private sector that ensures environmental and social considerations are embedded in all corridor activities.33

The commitment to sustainability extends below the ground to the very foundation of productivity: soil health. Recognizing that soil acidity is a critical, often invisible, barrier to crop yields in many parts of Africa, SAGCOT became a key partner in the “Guiding Acid Soil Management Investments in Africa” (GAIA) project.34 Supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), this initiative conducts research and promotes the use of agricultural lime to restore soil pH, a practice that has been shown to dramatically increase maize yields from 2 tonnes per hectare to as high as 7-8 tonnes.1 This focus on fundamental agronomy demonstrates a holistic approach to sustainable intensification—producing more on existing land to reduce pressure on forests and other vital ecosystems.

Clearing the Path: The Power of Policy Advocacy

Kirenga and the SAGCOT Centre understood that private investment and farmer training alone were insufficient. Sustainable transformation requires an enabling policy and regulatory environment. The Centre has served as a powerful and effective advocate for reforms that have systematically dismantled barriers to agribusiness growth.

These advocacy efforts have yielded tangible, high-impact policy wins. To reduce the cost of production for livestock farmers, SAGCOT successfully lobbied for VAT exemptions on animal feeds and poultry feed additives.36 To promote evidence-based farming, a similar exemption was secured for

soil testing kits.38 To protect nascent local industries from import competition, the Centre’s advocacy contributed to the East African Community’s decision to raise the common external tariff on products like

edible oils from 25% to 35%, a crucial measure to spur domestic production of sunflower and palm oil.39

Perhaps most importantly, SAGCOT has helped institutionalize the public-private dialogue. The establishment of Private Sector Desks within key government ministries created a formal, permanent channel for agribusinesses to raise concerns and collaboratively solve problems with regulators. This innovation moves the partnership beyond ad-hoc meetings to a structured, ongoing process, ensuring that the policy environment can continue to adapt to the needs of a growing agricultural economy.

| Metric | Achievement (as of 2024) | Source(s) |

| Total Investment Mobilized | USD 6.34 Billion | 1 |

| Public Sector Contribution | USD 5.02 Billion (79.2%) | 4 |

| Private Sector Contribution | USD 1.32 Billion (20.8%) | 4 |

| Smallholder Farmers Reached | Over 1 million | 1 |

| Jobs Created | Over 253,000 | 1 |

| Annual Farming Revenues (Illustrative) | USD 54.3 Million (FY2022) | 28 |

| Land Under Climate-Smart Agriculture | 1,285,404 Hectares | 28 |

Chapter 4: The Dawn of a New Epoch – The Nationwide Ambition of AGCOT

A National Mandate: From Corridor to Country

The resounding success of the SAGCOT model did not go unnoticed at the highest level of the Tanzanian state. On March 17, 2023, in a move that signaled a major shift in national economic strategy, President Samia Suluhu Hassan issued a directive to roll out the SAGCOT approach across the entire country.11 This marked the official birth of the Agricultural Growth Corridors of Tanzania (AGCOT), transforming a regional pilot into a national doctrine.

This presidential mandate was a watershed moment, elevating the corridor model from one of several development projects to the central vehicle for executing the nation’s agricultural ambitions. The SAGCOT Centre Ltd., under Kirenga’s leadership, was renamed the AGCOT Centre, formally tasked with being the operational and strategic engine for this nationwide expansion.2 Its mission was no longer just to cultivate success in the Southern Highlands but to replicate that success across new and diverse agricultural frontiers.

The New Frontiers: Charting the Mtwara, Central, and Northern Corridors

The expansion to AGCOT is not a monolithic, one-size-fits-all rollout. It is a sophisticated spatial economic strategy, deliberately targeting three new corridors, each with a unique agro-ecological profile, distinct infrastructure assets, and specific market opportunities. This approach reflects a mature understanding that successful agricultural development must be tailored to local conditions. As articulated by Agriculture Minister Hussein Bashe, the new corridors are being defined by their specific “ecology, economic activity, and export potential”.42

- The Mtwara Corridor: Agriculture Meets ExtractivesThe Mtwara Corridor in southern Tanzania presents a unique dynamic of immense opportunity and significant risk. It is already the focus of a major infrastructure development project designed to facilitate the export of the region’s vast natural resources, including natural gas, coal, iron ore, and uranium.43 The corridor’s agricultural potential is also significant, with fertile lands ideal for crops like cashews, which are a major export for the Lindi and Mtwara regions, as well as oilseeds and other staples.44 The primary opportunity lies in leveraging the massive public and private investment in infrastructure—particularly the expansion of the deep-water Port of Mtwara and the planned Mtwara-Mbamba Bay railway—for agricultural exports. However, this corridor also presents the greatest challenges. The convergence of large-scale agriculture and extractive industries creates a high potential for conflict over land and water resources. Furthermore, the corridor bisects the Ruvuma landscape, a globally significant wilderness area. Poorly planned development could pose a severe threat to its sensitive ecosystems, making the application of the IGG framework critically important here.45

- The Central Corridor: The Logistical HeartlandThe Central Corridor is Tanzania’s logistical backbone, a transportation route of road and rail that connects the port of Dar es Salaam to the country’s interior and the landlocked nations of the Great Lakes region (Burundi, Rwanda, Uganda, and eastern DRC).46 Its strategic value is less about unique crop potential and more about its role as a hub for processing, aggregation, and trade. The investment opportunities here are centered on value chains that benefit from efficient logistics and access to large domestic and regional markets. A prime example is the sunflower value chain, critical for producing edible oil and animal feed, which directly addresses Tanzania’s national priority of reducing its massive edible oil import bill.48 Other key value chains include grains and livestock. The AGCOT strategy for this corridor will likely focus on developing agro-processing industrial parks, modern warehousing, and strengthening value chain financing to capitalize on its strategic location.

- The Northern Corridor: The Horticultural PowerhouseThe Northern Corridor, encompassing regions like Arusha and Kilimanjaro, is defined by its high potential for high-value, export-oriented horticulture. With favorable climates and a history of agricultural innovation, this region is ideal for crops such as avocados, mangoes, fresh vegetables, and flowers.20 The success of dynamic, youth-led agribusinesses like Raha Vegetable Farm, which has strategically expanded its high-quality seedling production into the Northern Corridor, demonstrates the immense entrepreneurial energy and market potential in this sector.49 The primary opportunity is to tap into lucrative European and Middle Eastern markets. However, realizing this potential presents unique challenges. Export horticulture demands sophisticated and unbroken cold chain logistics, adherence to stringent international sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) standards, and careful management of water resources in a region where competition for water is already high.

| Corridor | Key Agricultural Profile & Priority Value Chains | Major Investment Opportunities & Strategic Challenges |

| Mtwara | Rich in natural resources. Priority value chains include cashews and oilseeds. Strong link to extractive industries (gas, minerals). | Opportunities: Leverage massive investment in port and rail infrastructure for agricultural exports. Challenges: High potential for land use conflicts between agriculture and mining; significant environmental risks to sensitive ecosystems. |

| Central | Serves as Tanzania’s primary logistical backbone to the Great Lakes region. Priority value chains include sunflower, grains, and livestock. | Opportunities: Develop agro-processing and logistics hubs; capitalize on regional trade and import substitution (edible oils). Challenges: Requires significant upgrades to existing infrastructure and warehousing systems. |

| Northern | High potential for export-oriented, high-value horticulture. Priority value chains include avocados, mangoes, flowers, and fresh vegetables. | Opportunities: Tap into lucrative international export markets; foster modern, tech-driven agribusiness. Challenges: Requires sophisticated cold chain logistics, high certification standards, and careful water resource management. |

The Grand Strategy: AGCOT as the Vehicle for Master Plan 2050

The nationwide expansion of AGCOT is not an isolated policy but the central implementation mechanism for Tanzania’s most ambitious long-term development vision: the Tanzania Agriculture Master Plan (AMP) 2050.2 The Master Plan sets forth breathtaking goals for the sector, aiming to grow the agricultural GDP to

USD 100 billion and achieve USD 20 billion in net agricultural exports by 2050.1

AGCOT is officially designated as “Flagship No. 7” of the AMP 2050, the national vehicle chosen to deliver these results.4 The strategy is to deploy the proven SAGCOT methodology—using the AGCOT Centre to deploy agile teams that will establish farmer-led, investment-driven cluster and commodity compacts—systematically across the new corridors. This approach represents a fundamental shift in national planning, moving away from broad, often diffuse, sectoral support policies toward a highly focused, spatially-concentrated economic strategy. By concentrating public infrastructure spending and policy support in these defined corridors, the government aims to create magnets for private investment, generating compounding returns and building specialized regional economies anchored in agriculture. This sophisticated form of industrial policy, using agriculture as its cornerstone, is Tanzania’s bold bet on its primary comparative advantage as the engine for its transformation into a resilient, prosperous, and globally competitive nation.

Conclusion: Cultivating a Legacy – Kirenga’s Vision for Tanzania’s Future

The journey from SAGCOT to AGCOT is more than the story of a successful development project; it is the story of a nation systematically unlocking its greatest potential. At the center of this narrative stands Geoffrey Kirenga, an architect who has not only designed a successful framework but has also painstakingly laid the human and institutional foundations required to build a lasting structure. His leadership has been the steady hand guiding a complex coalition of partners toward a shared vision, proving that transformative change is possible when pragmatism is fused with ambition.

Kirenga’s enduring philosophy is captured in a simple yet powerful formula: “Better policies = more investment = bigger impact”.53 This is the core logic that has driven every policy advocacy win, every partnership compact, and every investment mobilized. It is a doctrine born from a deep understanding that agriculture in the 21st century is not merely about farming; it is a complex system requiring an enabling environment where business can thrive, innovation can flourish, and smallholders can be meaningfully included. His vision extends beyond Tanzania’s borders, rooted in the conviction that agriculture is Africa’s “fastest route to shared prosperity”.53 By demonstrating a scalable model that lifts the poorest communities two to four times faster than growth in other sectors, he has provided a powerful counter-narrative to Afro-pessimism.

As AGCOT rolls out across the nation, the ultimate goal transcends mere food security. The objective is to achieve food sovereignty—a state where Tanzania not only feeds its people but also controls its food systems, becoming a resilient, economically diversified, and globally competitive agricultural powerhouse. The focus on developing value chains for wheat and edible oils is a direct strategy to reduce import dependency, while the push into high-value horticultural exports is a clear bid for a greater share of global markets.

The Tanzanian model, refined over a decade of trial, adaptation, and success, now stands as a powerful, evidence-backed blueprint for other nations. It demonstrates that with visionary leadership, a steadfast commitment to partnership, and a strategic focus on creating an enabling environment, the latent potential of African agriculture can be unleashed. Geoffrey Kirenga’s legacy will not be measured solely by the billions of dollars invested or the millions of tonnes harvested. It will be found in the transformed lives of a million farmers and counting, and in the enduring foundation he has helped build for a more prosperous and self-reliant Tanzania. He has been the architect of a revolution, one cultivated seed, one partnership, and one corridor at a time.