100Africa.com Feature

Tanga City Becoming a Global Blueprint for Youth-Led Urban Innovation

Tanga Yetu: How a Forgotten City Reinvented Itself by Believing in its Youth

The Unseen Transformation

By Anthony Muchoki

In the coastal city of Tanga, Tanzania, a quiet transformation is unfolding. It is a story led not by the grand gestures of mega-projects or foreign investors, but by the determined hands of carpenters, the focused minds of schoolgirls, the renewed hope of fishermen, and the innovative spirit of digital freelancers. At the heart of this metamorphosis is a simple yet profound idea: if a city truly listens to its young people, it can rebuild itself from the inside out. This is the story of Tanga Yetu, or “Our Tanga,” an initiative that began in 2019 with a bold vision to make Tanga a city where its youth are safe, empowered, educated, and connected.

This article chronicles the journey of the Tanga Yetu initiative, from its conception in the crucible of economic stagnation and youth disenfranchisement to its celebrated achievements in education, economic empowerment, and civic renewal. It examines the unique philanthropic model that catalyzed this change,a model that prioritized local ownership and systemic, city-wide intervention over traditional, top-down aid. Through a detailed analysis of its origins, projects, and impacts, the Tanga Yetu story emerges not merely as a local success, but as a potential blueprint for other secondary cities across Africa and the developing world. It is a testament to what happens when a community, its leaders, and their partners decide that a city’s young people are not a problem to be solved, but the very solution they have been waiting for.

Part I: The Sleeping Giant Wakes: A City in Waiting

1.1 A Legacy of Stagnation

To understand the necessity of an initiative like Tanga Yetu, one must first understand Tanga itself, a city of immense historical significance often described as a “sleeping giant”. Located on the Indian Ocean, Tanga has for centuries been an influential economic powerhouse and a strategic port on the East African coast. During the German colonial period, it was designated as the first township in German East Africa in 1891, serving as the center of colonial administration before the rise of Dar es Salaam. The Germans invested heavily in its infrastructure, building a port, a tram line, and the crucial Usambara Railway, which connected the agricultural interior to the sea and fueled a booming economy based on sisal production. Under British occupation and into the early years of independence, Tanga continued to thrive, becoming the second-largest city in Tanzania after Dar es Salaam.

However, the city’s fortunes took a dramatic turn in the post-independence era. The adoption of the Ujamaa socialist policy, combined with dwindling global prices for sisal, led to the collapse of the industry that was the city’s economic lifeblood. Factories closed, the port’s revenue plummeted, and Tanga lost its primary source of income. The once-bustling hub of commerce and industry entered a long period of economic stagnation. While the city retained significant assets, a major port, a railroad terminus, and a location at the heart of a fertile agricultural region, it struggled to find a new economic identity. The challenges faced by its youth in the late 2010s were not a recent phenomenon but a direct, generational echo of these past policy shifts and economic shocks. The “forgotten generation” was inheriting the long-term consequences of a city whose economic engine had stalled decades earlier.

1.2 The Youth Dilemma

By 2019, the consequences of this prolonged stagnation were most acutely felt by Tanga’s largest and fastest-growing demographic: its young people. The city presented a stark paradox of potential. It possessed fertile land, tourist attractions, and strategic infrastructure, yet for thousands of its youth, it was a city of dead ends.1 The core problem was not a lack of resources but a lack of catalysts to activate them, creating a generation that felt profoundly “stuck, waiting for a chance that might never come”.

This dilemma manifested in several critical areas. The educational system was in crisis. In schools across the city, students were often forced to sit two or three to a single desk, if a desk was available at all. Teachers faced the “painful reality” of trying to educate children in upper primary grades who still could not read a simple paragraph or solve a basic mathematical equation. This foundational failure in education had devastating downstream effects.

Outside the classroom, the situation was equally grim. The majority of youth had little to no access to skills training, viable income-generating opportunities, or even safe spaces for recreation and innovation. Youth unemployment, disillusionment, and depression were rampant in communities across the Tanga region. This was part of a broader regional trend of deteriorating social and economic services, which triggered mass migration of youth from rural areas into already overcrowded and under-resourced urban centers like Tanga. The city’s administration, for its part, was hampered by a lack of reliable and adequate data, making it difficult to formulate, monitor, and implement effective development programs to address the escalating crisis. A generation full of potential was being left behind, caught between a proud past and an uncertain future.

Part II: A Different Kind of Philanthropy: The ‘OurCity’ Doctrine

2.1 The Botnar Vision

The catalyst for change arrived in the form of Fondation Botnar, a Swiss philanthropic foundation with a distinct and forward-thinking mission: to improve the health and wellbeing of young people living in cities worldwide, with a particular focus on leveraging digital technologies and artificial intelligence (AI). The origins of Tanga Yetu are rooted in this global OurCity initiative, which was itself inspired by a personal tragedy. The foundation was established in memory of Octavian Botnar’s only daughter, who died at the age of 18. Her passing inspired the family to dedicate their wealth to giving young people worldwide the opportunities she never had. The foundation’s flagship program, the “OurCity” initiative, was conceived to support selected cities in implementing coordinated, multi-faceted programs to transform them into places where youth can thrive. A core element of this vision was the strategic decision to focus on secondary or “intermediary” cities, urban centers poised for rapid growth but not yet at the scale of megacities. This approach was designed to get ahead of the curve, embedding youth-centric development principles into the fabric of a city before the challenges of explosive urbanization became intractable.

2.2 Why Tanga?

Tanga was chosen as the very first city for the OurCity initiative, becoming what program coordinators would later call the “sandbox for all the other cities”. According to Dr. Hassan Mshinda, Fondation Botnar’s representative in Tanzania, the choice of Tanga was strategic: “Tanga was selected as a secondary city to proactively address the urbanization challenges overwhelming larger cities like Dar es Salaam. It offered unique advantages—smaller population density, strong infrastructure with high road coverage and water access, higher rates of formal employment, and above all, political commitment from city leadership.”

This confidence was symbolized in 2018, when Fondation Botnar held its first-ever board meeting outside Switzerland in Tanga—a clear endorsement of the city’s potential. The selection was a deliberate choice to collaborate with a city at a critical inflection point. Tanga was on the cusp of renewed economic growth but had not yet experienced the explosive, often chaotic, expansion seen in primary cities like Dar es Salaam. This presented a chance to proactively “build a more youth-friendly approach as the city continues to develop,” avoiding the well-documented mistakes in managing rapid urbanization elsewhere.

Choosing a secondary city like Tanga over a more complex metropolitan area was also a way to de-risk the ambitious, systemic model being tested. A smaller, more manageable urban system allowed the “sandbox” concept to be implemented with fewer confounding variables and a greater likelihood of demonstrating tangible, city-wide impact. Success in Tanga would not only benefit its residents but also create a proven, scalable model that could be adapted and replicated in more complex urban environments globally. In fact, Tanga Yetu was the first OurCity initiative, and its impacts later led to the introduction of similar programs in cities in Romania, Colombia, Ecuador, and Ghana.

2.3 An Unconventional Approach

What truly set the initiative apart was its unconventional philosophy, which represented a radical departure from traditional, top-down development aid. The approach was fundamentally place-based and systemic. Instead of funding a single, siloed project to be implemented across many cities, the goal was to invest in a whole city, nurturing a diverse portfolio of interconnected projects that collectively addressed the ecosystem of youth wellbeing. This city-building approach was rooted in the principles of “youth agency and community co-design”.

The power dynamics of traditional philanthropy were deliberately inverted. The process did not begin with a pre-determined agenda from Geneva. Instead, it started by asking the young people and local stakeholders of Tanga a simple question: what were their dream projects for their city?. The early projects reflected these urgent local needs, focusing on interventions like road safety for schoolchildren and life skills through sports. To facilitate this, the program established Youth Advisory Committees in each of Tanga’s 27 wards, creating hyper-local, peer-led forums where young people could speak freely about their challenges and aspirations. These initial workshops and consultations were not a formality; they were the bedrock of the entire initiative, ensuring that the mandate was authentically driven by local needs and aligned with Tanzania’s national strategies for job creation and education.

2.4 The Architect: Dr. Hassan Mshinda

The successful translation of this high-level philanthropic vision into a tangible, locally-owned program required a unique leader on the ground. That leader was Dr. Hassan Mshinda, Fondation Botnar’s representative in Tanzania. Dr. Mshinda was a “keystone individual,” whose specific and rare combination of skills made him the indispensable bridge between the international foundation and the local community.

His resume was formidable. With a PhD in Epidemiology from the University of Basel, he was a celebrated scientist and former Director of the prestigious Ifakara Health Institute. Crucially, he had also served as the Director-General of Tanzania’s Commission for Science and Technology (COSTECH), giving him an unparalleled understanding of the country’s national innovation ecosystem and policy landscape. This blend of international credibility, national-level policy experience, and deep local understanding allowed him to navigate the complexities of multi-stakeholder collaboration with unmatched dexterity. He was instrumental in every key stage: selecting Tanga, assembling the diverse coalition of partners, designing the programmatic framework, and leading its execution, all while steadfastly championing the principle of local ownership. His guiding philosophy was one of collaboration over competition, working to ensure all partners shared the objective of improving youth wellbeing without getting caught up in “competing flags”. This ethos was critical in fostering the trust and cooperation that would become the hallmark of Tanga Yetu.

Part III: Building from the Ground Up: A Seat at the Table

Before any complex interventions in digital literacy or entrepreneurship could be contemplated, the Tanga Yetu initiative first had to address the most fundamental and visible barrier to progress: the dire state of the city’s educational infrastructure. The strategy that emerged demonstrated a profound understanding of community development: change begins by restoring dignity.

Table 1: The Tanga Yetu Initiative: Key Achievements at a Glance (Phase I)

|

Thematic Area |

Intervention |

Key Quantifiable Outcomes |

|

Education |

School Furniture |

4,090 desks & 7,691 tables/chairs supplied |

|

16,000+ students with improved learning environments |

||

|

Teaching at the Right Level (TaRL) |

630 students in numeracy remediation (405 graduated) |

|

|

473 students in literacy remediation (377 graduated) |

||

|

Economic Empowerment |

Digital Skills |

100 youth trained in digital skills |

|

Sh 10 million combined income earned by digital trainees in 6 months |

||

|

Agribusiness & Aquaculture |

360+ youth trained in agriculture & aquaculture |

|

|

Savings groups accumulating over Sh 13 million |

||

|

Child Safety & Health |

Child Protection |

104 anti-abuse clubs established in schools |

|

80,000+ people reached with awareness campaigns |

||

|

Road Safety |

10,000+ schoolchildren benefiting from road safety improvements |

3.1 The Dignity of a Desk

The initiative’s first major undertaking was the school furniture project, a powerful and foundational intervention that addressed the stark reality of students sitting on floors or crammed together at broken desks. The scale of the project was significant: 4,090 desks were supplied to primary schools, and 3,846 tables along with 3,019 chairs were delivered to secondary schools, directly improving the learning environment for over 16,000 students.

However, the “how” was just as important as the “what.” In a move that exemplified the program’s core philosophy, the furniture was not simply imported or procured from a large, external supplier. Instead, it was built by local carpenters in Tanga City, a workforce that included 113 youths, 39 adults, and 10 persons with disabilities.5 This created a virtuous, circular model of development. The investment not only solved a critical problem in the education sector but also simultaneously created jobs, transferred carpentry skills, strengthened the local economy, and fostered a deep sense of community ownership over the solution.20

The impact was immediate and profound. Teachers reported a notable improvement in classroom order and student focus. The simple act of providing a proper seat restored a sense of dignity to the learning process. This “Dignity First” approach was a strategic masterstroke. By starting with a highly visible, universally understood, and dignity-affirming intervention, the program built immediate trust and goodwill with students, teachers, and parents. This foundational success created the social capital and positive momentum required to introduce more complex pedagogical changes.

3.2 Teaching at the Right Level (TaRL)

With a more conducive learning environment established, Tanga Yetu rolled out its next major educational intervention: the “Teaching at the Right Level” (TaRL) approach, implemented across 20 primary schools. This evidence-based method, borrowed from India, directly tackled the crisis of low literacy and numeracy.14 The process began with an assessment of over 2,000 students in grades 3 through 6. Based on the results, students were grouped by their actual ability level rather than their grade, allowing teachers to provide targeted support where it was needed most.

Teachers were trained to use interactive and engaging methods—including songs, games, and storytelling—to help struggling learners catch up and build confidence. The results were remarkable. Of the 630 students enrolled in numeracy remedial sessions, 405 successfully graduated after mastering basic operations. In literacy, 473 students were enrolled, and 377 graduated with improved reading fluency, an 81% success rate.

The statistics come to life through the powerful testimonials of those who witnessed the change firsthand. Mwajabu Ally, a teacher at Majengo Primary School, reflected on the transformation: “Using songs, games, and interactive teaching methods, children who once struggled to read and count are now excelling”. The impact resonated deeply with parents as well. One mother at Kana Primary School, who was initially hesitant to enroll her child, recounted her journey from despair to pride: “I used to think my son was bewitched. Teachers said he had learning difficulties. Now he reads newspapers to me”.

3.3 A Note of Nuance

While the TaRL program was celebrated for its impressive results, the approach was not without its critics. Online discussions among Tanzanians revealed some apprehension about the methodology, particularly the practice of moving students to lower grades based on ability assessments. Commentators raised valid concerns that such a move could be perceived as a demotion, potentially lowering a child’s self-esteem and creating a feeling of being left behind. They argued that alternative approaches, such as separating students into different ability streams within the same grade level, might achieve similar academic results without the associated psychological risks. This perspective adds a crucial layer of nuance, demonstrating that even highly effective development interventions can involve complex trade-offs and spark important debates about the best path forward.

Part IV: Forging New Pathways: Skills for a Modern Tanga

With the educational foundation strengthened, Tanga Yetu turned its attention to the pressing challenge of economic empowerment, creating a diversified portfolio of opportunities designed to equip youth with skills for the future while leveraging the city’s unique assets.

4.1 The Digital Leap

Recognizing the growing importance of the digital economy, the initiative launched a program to train 100 young people in high-demand skills such as graphic design, content creation, and online freelancing. In an innovative and accessible approach, much of the training was designed to be completed using mobile phones, removing the barrier of needing access to a computer. This program was championed by local digital leaders like Gillsant Mlaseko, who promoted digital marketing training to help small businesses grow.

The economic impact was swift and substantial. Within just six months of completing their training, the participants had earned a combined income of 10 million Tanzanian Shillings. Many went on to secure clients, mentor other youth, or launch their own digital businesses. The transformative power of these new skills is captured in the story of Zainab Msafiri Msuya, a 33-year-old mother of two. For her, joining the digital skills project was a life-altering experience that provided a clear path to a better and more secure future for her family.

4.2 The Blue and Green Economy

The initiative also crafted programs that tapped into Tanga’s rich natural heritage—its fertile lands and coastal waters.This strategy did not impose a single economic model but instead offered multiple pathways tailored to Tanga’s actual economic DNA. Over 360 youth received training in a range of “green” and “blue” economy sectors, including horticulture, poultry farming, fisheries, seaweed farming, and crab fattening.1 This diversified approach catered to a wide array of interests and skills, building a more resilient local economy.

A standout success was the poultry project, which became a powerful engine for youth entrepreneurship. The program was anchored by a strategic partnership with Elizabeth Swai, a trailblazing entrepreneur and founder of AKM Glitters Company Limited, which specializes in breeding high-yield Kuroiler chickens. With support from Tanga Yetu and land provided by the Tanga City Council, Ms. Swai established five brooder houses, creating a hub for youth to learn the poultry business. The project’s structure empowered participants to become business owners. In one instance, youth groups collectively saved 30 million Tanzanian Shillings, which they then distributed amongst themselves to launch their own individual poultry businesses.

This model of collective saving leading to individual enterprise was a critical mechanism for success across the initiative. Youth Savings and Loans Associations became incubators for financial literacy, social trust, and shared investment. These groups were not merely about saving money; they were community-owned alternatives to traditional finance, providing the micro-capital necessary for youth to scale their ventures independently. In another project, savings and lending groups accumulated over 13 million Shillings, which they reinvested into their private ventures.

The impact on the fisheries sector was equally transformative. For many young people in coastal Tanga, life was a daily struggle with no clear purpose. This changed dramatically for participants like Shali Bakari. “In the past, we would wake up not knowing where to go or what to do. Life was a struggle,” he recalled. “But after receiving the boat and fishing gear from TangaYetu, everything changed. Now, we have a purpose—we wake up, go to the sea, and return with something to support our families”.1

4.3 The Mindset Shift

Underpinning all these sectoral interventions was a cross-cutting focus on fostering an entrepreneurial mindset. One project, specifically targeted this “mindset change” and reached 1,036 young people. The results were staggering: a midline survey revealed that 77% of participants had either started a new business, secured employment, or both. The project had a dramatic effect on poverty levels as well. While only 42% of participants were above the national poverty line at the project’s baseline, that figure had risen to 72% by the halfway point. This demonstrated that providing skills and capital was only part of the equation; nurturing self-belief, confidence, and a proactive approach to problem-solving was the essential ingredient that turned training into tangible economic progress.

Part V: A City Reimagined: Safe Spaces and Smart Systems

The Tanga Yetu initiative extended its reach beyond individual skills and into the very fabric of the city, transforming public spaces, enhancing safety, and building the technological capacity for smarter, more responsive governance. The strategy recognized the symbiotic relationship between physical environments (“hard” infrastructure) and social programming (“soft” infrastructure), understanding that one is most effective when paired with the other.

5.1 Reclaiming Public Space

A powerful symbol of this urban renewal was the revitalization of Jamhuri Park. Once an abandoned and neglected area, it was transformed into a vibrant youth economic zone, now home to over 50 active young vendors. This project was a testament to the principle that when young people are trusted to lead, they can breathe new life into the spaces around them. A renovated park is just a park; a renovated park that is also a designated hub for youth enterprise becomes a catalyst for community-wide opportunity. The co-creation model used for the park was so successful it was later embraced by other regions, leading to the establishment of similar traders’ markets in cities like Dodoma and Arusha.12

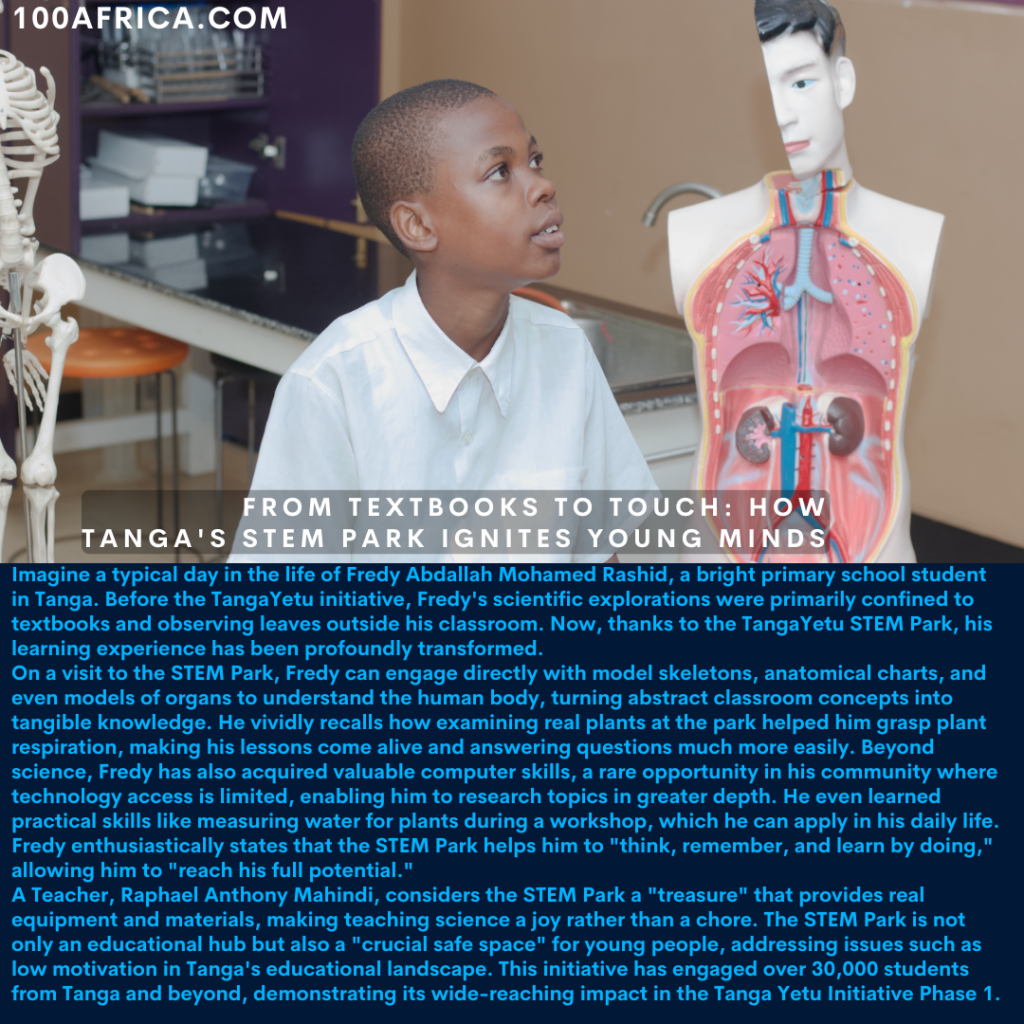

Another flagship innovation was the establishment of East Africa’s first STEM Park in Tanga. This hands-on, interactive learning environment was designed to make science, technology, engineering, and mathematics exciting and accessible to children as young as six. Combining play with modern gadgetry like VR and drones, the park provided informal education to over 30,000 young people through outreach programs, sparking curiosity and nurturing the next generation of innovators.

5.2 Enhancing Safety and Protection

Improving the wellbeing of Tanga’s youth also meant creating a safer environment for them to grow and learn. The initiative established 104 anti-abuse clubs in schools, creating peer-led networks to raise awareness and provide support. These efforts were complemented by broad public awareness campaigns that reached over 80,000 people and direct interventions that rescued 12 children from child labor.

Physical safety was also prioritized through the Road Safety City Project. This program implemented crucial infrastructure improvements in and around eleven school zones, including new footpaths, signage, and designated safety areas, directly benefiting the daily commutes of over 10,000 schoolchildren.1

5.3 Building a “Smart” City

A core tenet of the Fondation Botnar philosophy is the use of data and technology to improve urban governance. In Tanga, this translated into a suite of projects designed to build a “smarter” city from the ground up. The Uhurulabs project used drones and satellite imagery to produce high-resolution maps of Tanga, providing planners with unprecedented detail to improve the delivery of urban services.

This data-gathering capacity fed into a larger strategic goal: the establishment of a “Data Centre” or “City Observatory”. This platform, the first of its kind to be certified by UN-HABITAT in East Africa, was designed to embed a culture of evidence-informed decision-making directly within the Tanga City Council. The emphasis on data was not merely about technological efficiency; it was a long-term strategy for legitimacy and sustainability. In a remarkable display of entrepreneurial spirit, the youth who participated in data collection for the observatory formed their own organization, OMAT (Okoa Maisha kwa Takwimu – Save Life Through Data), and successfully secured their first contract with the World Bank.12 By building the local capacity to collect, analyze, and act on data, the initiative was equipping the city’s own government with the tools to plan future interventions independently, a critical step toward ensuring the program’s legacy endures. This work was supported by local experts like Prof. Ally Namangaya, a land-use planning specialist from Ardhi University, and John Kajiba, an IT and data analysis expert, ensuring that the capacity being built was deeply rooted in Tanzanian expertise.

Part VI: The Unseen Harvest: A Legacy of Belief

6.1 The Hardest Thing to Measure

While the quantifiable achievements of Tanga Yetu are impressive, the desks built, the income earned, the students graduated—they do not tell the whole story. The initiative’s architects and observers consistently point to a more profound, albeit less tangible, outcome. As one report concluded, “The most powerful change TangaYetu has sparked may be the hardest to measure: belief”. This was the unseen harvest of the program’s work: a fundamental shift in mindset that cultivated a sense of agency, possibility, and collective ownership across the city.

6.2 A Shift in Mindset

This transformation in belief was evident across every segment of the community touched by the initiative. For the youth, it was a journey from the despair of being “stuck” to a newfound sense of purpose and control over their destinies. This is the change articulated by the young fisherman Shali Bakari, who went from aimlessness to providing for his family with pride. For educators, it was a professional revitalization, moving away from the monotony of rote lectures to the joy of guiding engaged, confident learners, a shift passionately described by teacher Mwajabu Ally. And for parents, it was a transition from resignation to hope, perfectly captured by the mother who saw her son, once dismissed as having learning difficulties, blossom into a reader of newspapers.

This reframes the very definition of a successful development outcome. While traditional metrics focus on income or test scores, Tanga Yetu demonstrates that “belief”or agency is a primary, not secondary, goal. It is the foundational asset upon which all other sustainable progress is built. The initiative’s true success was not just in giving people skills; it was in giving them a compelling reason to believe that those skills mattered and that they, themselves, could shape their own futures.

6.3 The Core Principles of Transformation

Distilling the lessons from Tanga Yetu reveals a set of core principles that drove its success. At the forefront was a commitment to human-centered design, ensuring that programs were developed with, not for, the community. The strategic decision to invest in a secondary city like Tanga proved vital, allowing for a more nimble and impactful intervention that could serve as a model for others. The creative leveraging of public spaces, the fostering of multi-stakeholder collaboration over competition, and the empowerment of local government were all critical ingredients.

This final point—the unwavering support of the local government, cannot be overstated. The Tanga City Council, under the leadership of leaders like Mayor Abdurahman Shiloow, was not a passive recipient of aid but an active and essential partner in the initiative. This deep collaboration was crucial for overcoming bureaucratic hurdles and ensuring that the projects were aligned with the city’s long-term development vision, embedding the spirit of Tanga Yetu into the very machinery of civic governance.

Part VII: The Horizon: Sustaining ‘Our Tanga’

7.1 The Next Chapter: TangaYetu Phase II

The success of the initial phase has paved the way for an ambitious expansion. TangaYetu Phase II was officially launched with the introduction of new projects, eventually growing the portfolio to 13 active initiatives and beyond, making it one of the largest coordinated youth-focused efforts in the city’s history.34 This next chapter demonstrates the program’s ability to learn and evolve, deepening its focus on critical areas that emerged from the first phase.

New projects show a more nuanced understanding of the ecosystem of youth wellbeing. “Kijana Togora: Tunakusikiliza” (Youth Speak Up: We Are Listening) directly tackles the often-overlooked issues of mental health, substance abuse, and sexual and reproductive health through safe spaces and digital platforms. “Pamoja Tuwalinde” (Together We Protect Them) aims to strengthen child protection systems across all 27 city wards. Another project trains Youth Accountability Advocates to educate their peers on civic rights and ensure youth voices are included in local governance decisions. This expansion signifies a move from foundational interventions to addressing more complex social and civic challenges.

7.2 The Paramount Challenge: Sustainability

As Tanga Yetu looks to the horizon, it faces the single most critical challenge for any externally funded development initiative: “ensuring that youth-led initiatives continue after the funding cycle ends”. The long-term success of the program will not be measured by the achievements of its first five or ten years, but by what remains and continues to grow in the decades that follow. From its inception, the architects of Tanga Yetu have been acutely aware of this challenge and have woven a strategy for endurance into the program’s design.

7.3 A Strategy for Endurance

The initiative’s approach to sustainability is multi-faceted and proactive. First is the continued strengthening of local government capacity. By embedding data systems like the City Observatory and co-design methodologies within the Tanga City Council, the program aims to make evidence-based, youth-centric planning a permanent feature of local governance.

Second is the investment in human capital through mentorship pipelines. The goal is to create a virtuous cycle where the first generation of successful youth entrepreneurs and leaders can guide and support the next cohort, building a self-perpetuating ecosystem of local expertise.

Third is the embedding of community-led monitoring systems. By empowering the community to use platforms like the City Observatory to track progress themselves, the initiative fosters a culture of accountability that is driven from the bottom up, not the top down.

Finally, there is a strong emphasis on fostering self-sustaining business models. Projects like the poultry and fisheries enterprises are designed to be profitable ventures. To support this, the Tanga City Council has pledged to establish a city fund to provide the follow-on capital, for land, incubators, or equipment—that young entrepreneurs need to scale their businesses beyond the startup phase, creating a bridge from philanthropic support to sustainable commercial success.

A Replicable Blueprint?

The story of Tanga Yetu is a powerful and compelling case study in urban transformation. It is a narrative of a city that, faced with the legacy of economic decline and a generation of disenfranchised youth, chose a path of radical hope and collaborative innovation. By inverting the traditional aid model and placing young people at the very center of the design process, Tanga and its partners have unlocked a wellspring of local potential, leading to tangible improvements in education, economic opportunity, and civic life.

The initiative offers a potent model for other secondary cities facing the dual pressures of a youth bulge and rapid urbanization. It demonstrates that transformation does not come from top-down announcements but from making thousands of small, smart, human-centered decisions over time. The path forward is not without its challenges, chief among them the long-term sustainability of its many interventions. Yet, the profound shift in belief—the cultivation of agency, purpose, and a shared sense of ownership over the city's future—provides the strongest foundation for enduring success. The quiet revolution in Tanga sends a clear message to the world of development: "youth are not a problem to solve—they are the solution we have been waiting for".

VOX POP -Youth Empowerment & Economic Growth

1. Poultry Power: From Uncertainty to Prosperity

“Through the Poultry Project under the TangaYetu Initiative, I learned how to manage a poultry business and gained confidence in my abilities to support myself and my family. The skills I’ve learned have opened doors I never thought possible, and being part of a savings group has given me financial security and hope for a better future.” — Mohamed Juma Athumani, Participant, TangaYetu Youth Poultry Project

2. Lasting Knowledge: Youth Leading the Way

“TangaYetu was the foundation that helped me turn a simple idea into a thriving poultry project… The training from TangaYetu has shaped who we are today. We’re not just poultry farmers; we’re confident, capable young entrepreneurs ready to lead the way in our community… If TangaYetu ever had to end, I would remember the knowledge they gave us, because knowledge doesn’t fade. The skills and confidence they instilled in us have changed our lives.” — Paul Divason Sikombe, Chairperson, Unity Youth Group and Poultry Farmer

3. Digital Skills: Empowering a New Generation

“My goal isn’t just to benefit myself. I want to share what I’ve learned with others so they can benefit from the same opportunities… The skills I gained didn’t end with me. I’m determined to teach others so they won’t miss out on what I was fortunate enough to learn.” — Zainab Msafiri Msuya, Digital Entrepreneur and Mentor, TangaYetu Digital Employment Opportunities Project

4. Farming with Purpose: A Path to Family Stability

“These crops have changed my life. I now know how to plan my planting, use fertilizers effectively, and manage pests to maximize yields. Before, I farmed aimlessly, but now I farm with purpose… The income earned from my agriculture activities has brought stability to my family. We no longer fear going without food. My wife and children now believe in my work because they can see the results.” — Hamisi Shabani, Farmer, Kiomoni Ward, TangaYetu Agribusiness Project

5. Women Thrive: Breaking Barriers in Fishing

“We used to be limited by small wooden boats. But thanks to TangaYetu, we now have a fiber boat that allows us to venture further, increase our catch, and improve our income… When women come together, we don’t just survive, we thrive. And we make sure no girl is left behind.” — Bay Juma, Treasurer, Maua Group (Women’s Fishing Collective)

6. Local Businesses: Building Trust, Securing Growth

“This project not only allowed us to contribute to the education sector but also provided an opportunity for my business to grow. We earned trust and acquired additional government contracts due to the quality of our work.” — Khalid Salim Abed, Founder, Sihaba Company Limited, Desks, Tables and Chairs Project

7. Tanga Delivery: Digital Mapping Fuels New Ventures

“Before TangaYetu, Tanga didn’t have a strong digital presence… But once Tanga was mapped, I realized there was an opportunity to launch Tanga Delivery and connect the city in a new way.” — Rock John, Entrepreneur, Tanga Delivery

8. BSF Farming: Sustainable, Profitable Innovation

“It’s a sustainable, profitable venture that can help many… [They are] a perfect protein substitute, cutting down on the need to purchase fishmeal, which often contains sand and other impurities.” — Irene Charles Kiariro, Black Soldier Fly Farmer

9. Carpenter’s Success: Desks Create New Businesses

“Through this project, I worked with Nyere Secondary, Chumbageni, and Magaoni schools to create 400 desks and chairs. The work employed seven youths in my workshop, giving them earnings that enabled them to start their ventures.” — Amani Zindwani Mchome, Local Carpenter, Desks, Tables and Chairs Project

Education & Skill Development

10. Dignity in Learning: Desks Transform Schools

“The project has given our children dignity. They no longer sit on dusty floors, and we, as parents, see the pride in their eyes when they come home and talk about their desks. It’s more than just furniture—it’s their confidence that’s been built.” — Rashid Majaliwa, Parent, Kisimatui Village, Desks, Tables and Chairs Project

11. STEM Park: Sharpening Minds for the Future

“The STEM Park has so many benefits for me. It helps me think, remember, and learn by doing… The STEM Park has sharpened my mind and improved my thinking abilities. I’ve also learned how to use a computer, which is a skill I’ll need in the future.” — Fredy Abdallah Mohamed Rashid, Primary School Student, TangaYetu STEM Park

12. FabLab: Technology Driving Community Development

“Our main goal is not just skill acquisition, but the effective use of those skills to drive community development. We believe that technology is the future of any economy, and through TOIO, we want to make Tanga part of that future.” — Sahil Abdulahman Ismail, Instructor, Tanzania Open Innovation Organization Project (TOIO) Fabrications Lab

13. TaRL: Innovative Teaching, Student Excellence

“Using songs, games, and interactive teaching methods, children who once struggled to read and count are now excelling… Now, when students sit down, they’re focused and ready to learn. As a teacher, I can manage my lessons better, and the students are performing much better. This initiative has been a blessing.” — Mwajabu Ally, Teacher, Majengo

14. Mayor’s Vision: Revolutionizing Learning Environments

“These desks and chairs have revolutionized learning. You can see the change in how children carry themselves. They’re more attentive, more comfortable, and their performance has improved dramatically.” — Hon. Abdurahman Omary Shiloow, Mayor of Tanga City, Desks, Tables and Chairs Project

Community Well-being & Governance

15. Courage and Safety: Rebuilding Lives

“After enduring years of abuse, I finally found the courage to report my situation. The support I received from the program helped me leave my abuser and start a new life. I am grateful for the safe spaces they created.” — Amina (name changed for privacy), Survivor of Violence, Combating All Forms of Violence Against Children and Adolescents in Tanga City Project

16. Hope Reborn: Empowering the Vulnerable

“I used to feel like I had no future. But through this program, I found people who believed in me and gave me the tools to turn my life around. Now, I want to help others do the same… This program gave me hope when I had none. Now, I want to be the hope for someone else.” — Ismail, Former Gang Member, Mental Health Awareness and Substance Abuse Recovery Project

17. Youth Voice: Direct Impact on Governance

“Before YAG and GOYN, youth-related matters were only addressed through community development officers. Now, we have direct communication, and we’re seeing results.” — Abdallah Rashid Mselem, Chairperson, Youth Advisory Group (YAG), Global Opportunity Youth Network (GOYN) project

18. Child Safety: Building a Legacy of Freedom

“A child’s safety is not just about infrastructure—it’s about giving them the freedom to dream and learn without fear. And that’s a legacy worth building.” — Ramadhani Nyanza, Project Coordinator, AMEND, Safe and Healthy Journeys to School for Children and Adolescents project